“Churchill Book Collector” implies a certain staple in our inventory. Namely books. But many of you know that there is more to our inventory than merely books – including ephemera, correspondence, and… photographs.

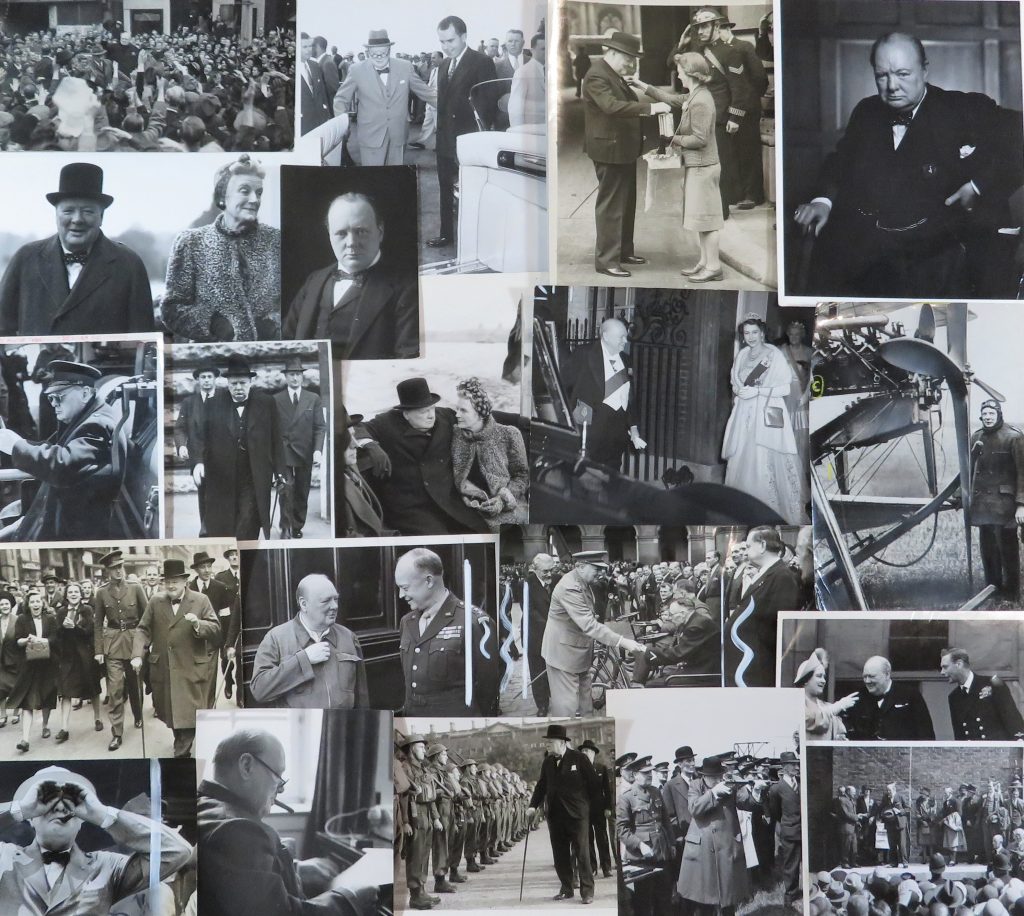

Over the past year, we have acquired a treasure trove of roughly 300 original press photographs of Winston Churchill, spanning the latter half of Churchill’s life, from the 1920s through 1964. In this blog post we give a brief history of these remarkable repositories of history and a preview of our offerings to come.

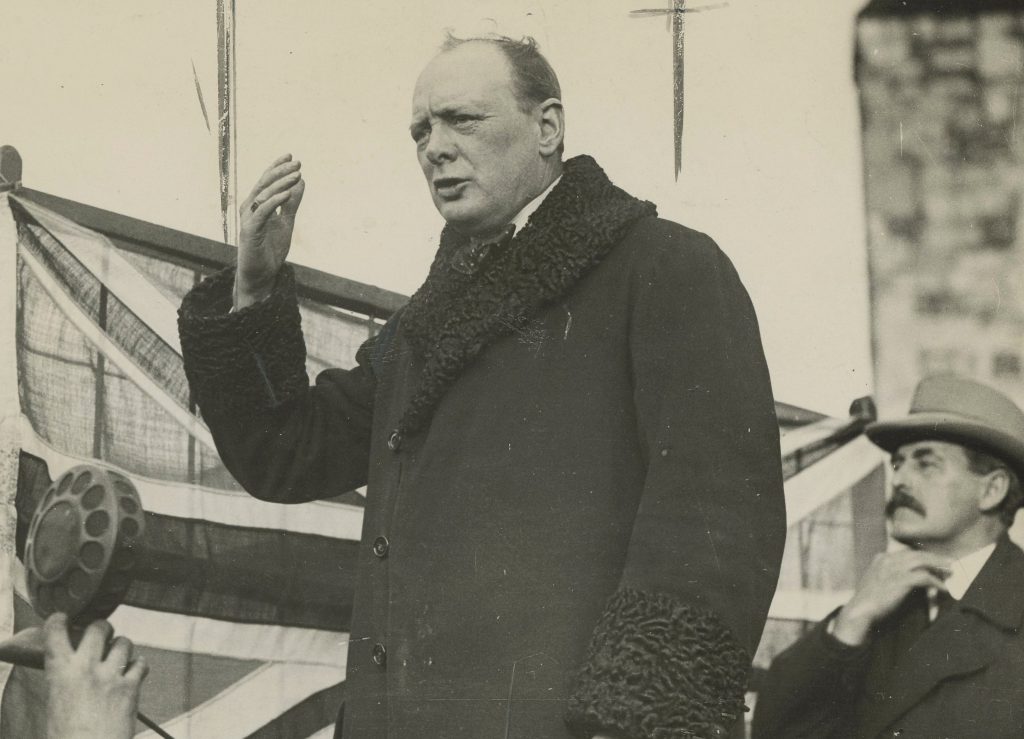

Through this remarkable collection of photographs we glimpse the vigorous ambitions of the young Cabinet minister, the isolation of his wilderness years, his leadership during the war years, his sojourn as leader of the opposition, his valedictory second premiership, and his final decade, when Churchill passed “into a living national memorial” of the time he had lived and the Nation, Empire, and free world he had served.

We have just listed the first tranche of 60 of these 300 photographs. These 60 original press photographs span Churchill’s resignation from his second and final premiership in April 1955 to his death in January 1965.

Churchill’s long career coincided with the evolution and ascendance of photojournalism. He witnessed its early years, remarking “It is the misfortune of a good many Members to encounter in our daily walks an increasing number of persons armed with cameras to take pictures for the illustrated Press which is so rapidly developing.” (letter of 26 June 1911 to Alfred Lyttelton) And during the war years he was a frequent subject of photojournalism’s golden age – often with noteworthy and occasionally with truly iconic results.

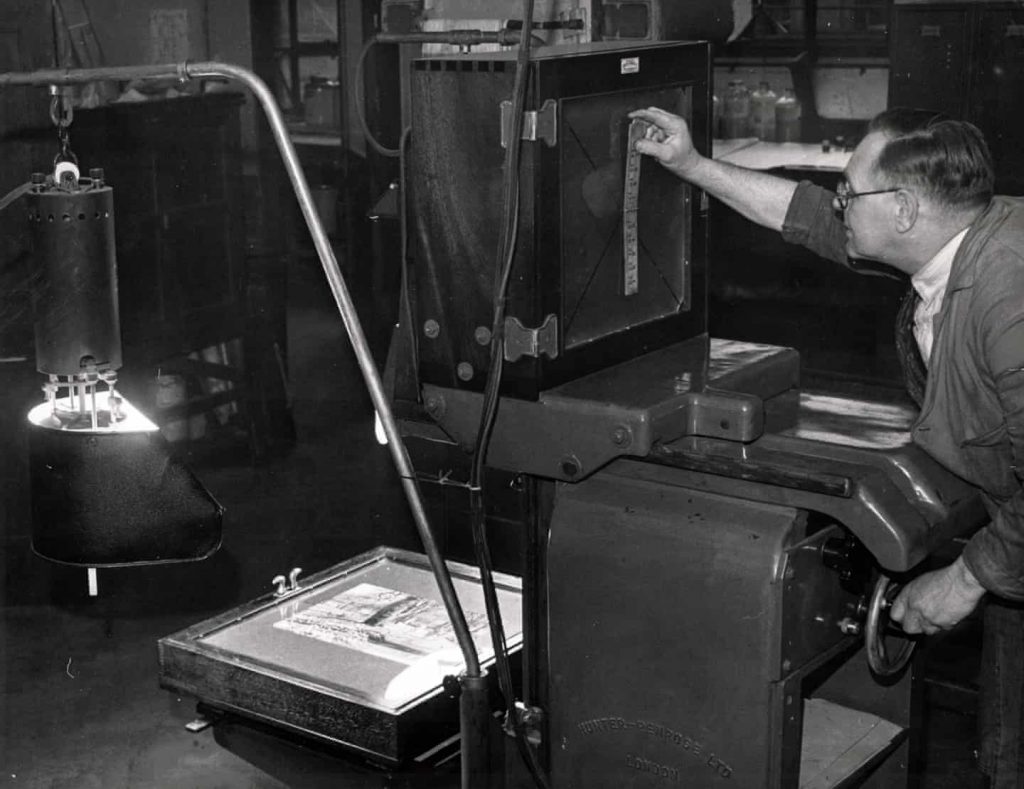

Soon after the development of photography in the mid 19th century, newspapers began to look for ways to supplement the written word with this new technology. For decades the only means of publication was through highly labor-intensive wood engravings reproduced by hand. In March 1880 – just half a decade after Churchill’s birth – The Daily Graphic of New York became the first paper to publish a halftone reproduction of a photograph. The development of this new photochemical reproduction process allowed for papers to begin to easily and quickly publish photographs.

These newly illustrated newspapers were an immediate success with the public, and a new profession, the photojournalist, was born. Only the largest newspapers had the resources necessary for in-house photographers, so news agencies were quickly established to meet the demand. Naturally, there was great incentive for each news agency to be the first to have available a photograph of a major event. All modes of transportation – including carrier pigeons – were used to speedily transport negatives to the agency bureaus where they were developed out and supplied to papers. This intense competition led to the Associated Press’s development of the most important photojournalistic inventions since the halftone, the Wirephoto.

Developed in 1921, AP’s Wirephoto allowed for the first “instantaneous” transmission of visual images. The technology involved scanning photographic images and translating the image density into audio tones which could then be transmitted over dedicated phone lines. The audio transmission could then be received by special equipment that would translate the signal back into light, exposing a silver gelatin photographic support that could be processed in the dark room. Until 1954 – the year before Churchill would relinquish the premiership for the second and final time – nearly all press photos were printed using this process.

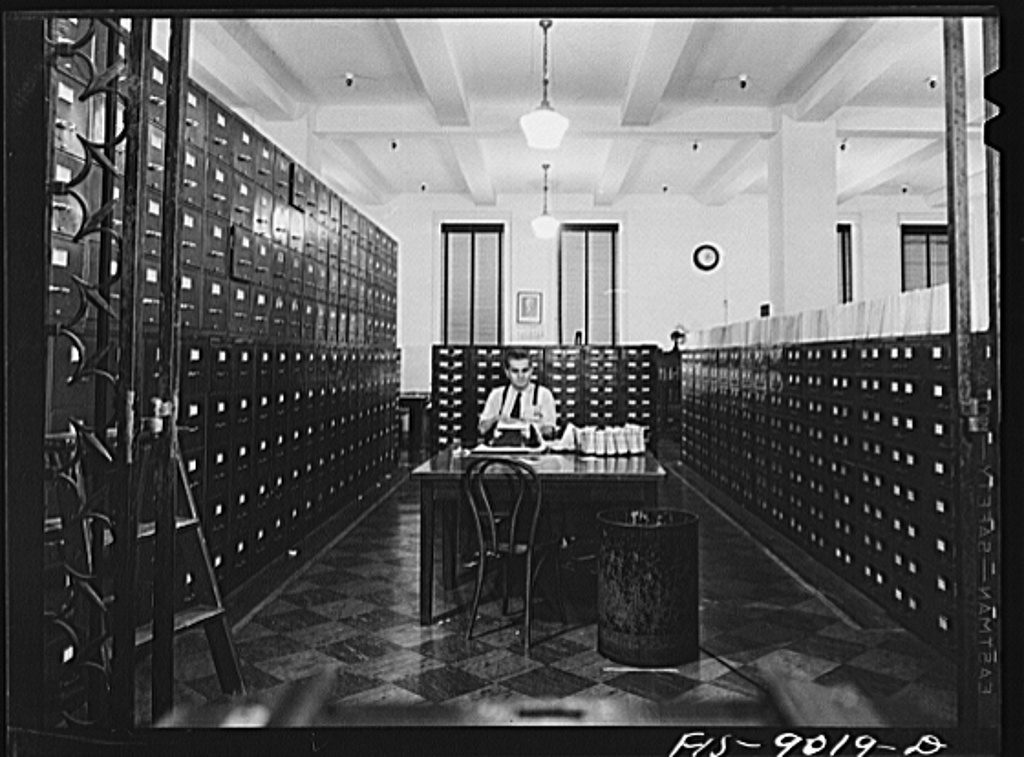

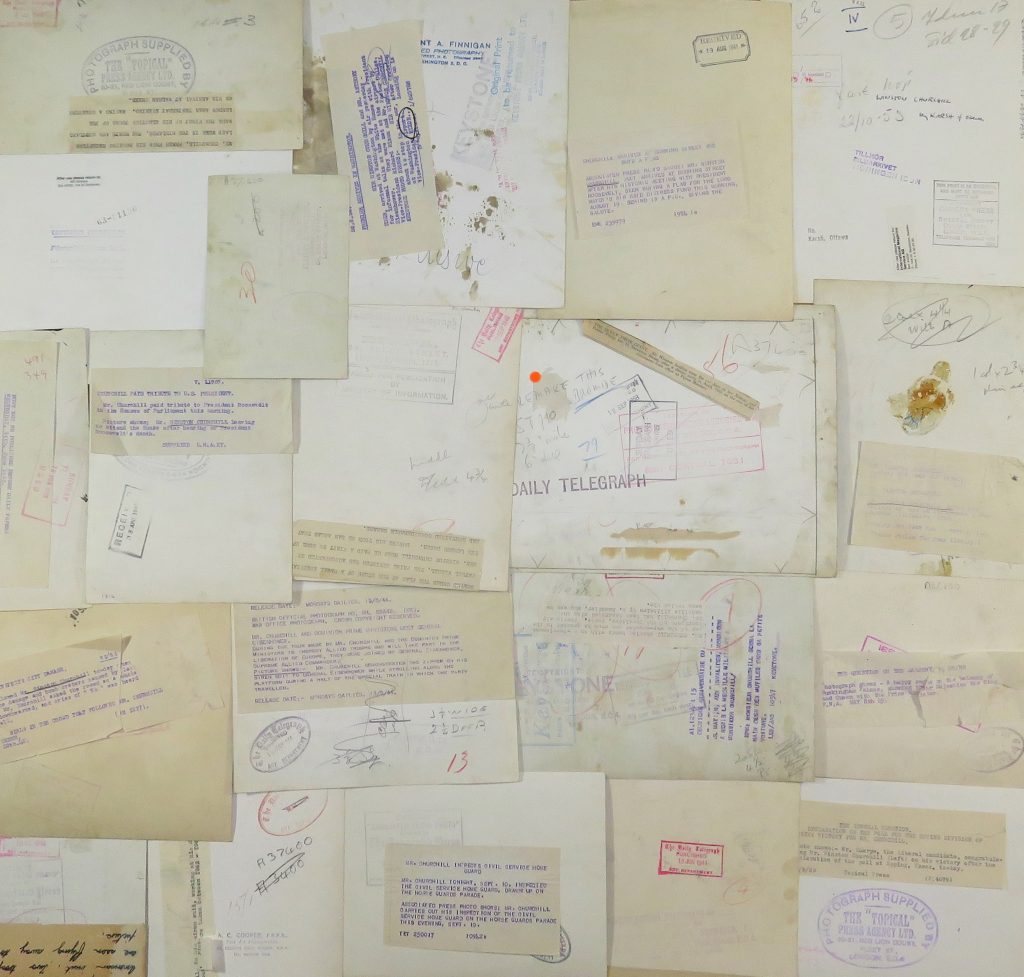

As newspapers began to collect photographs from staff photographers, news agencies, and third-party photographers expansive archives, called “photo morgues”, were established. Within these archives physical copies of all photographs published or deemed useful for future use were filed away. These archives often grew to hold more than a million images. Most newspapers’ filing processes included stamping the verso of each image with the copyright holder, publication notes, typed captions (often supplied by news agencies), reproduction notes, and clippings of the image’s appearance in print. During wartime censor information was occasionally also included. As a result, photo morgues serve as vast, rich archives of primary historical sources.

In addition to their historical importance, photo editing techniques of the early 20thcentury often make these unique and aesthetically fascinating visual objects. Before Photoshop made such edits possible at the click of a button, newspapers’ photo departments would often take brush, paint, pencil, and marker to the surface of photographs. These additions ranged from the mere adjustment to the total re-contextualization of a photo.

With the addition of paint these photographs become not only repositories of historical memory and technological artifacts but also striking pieces of vernacular art. And as the photographs were archived for reference and potential re-use, extensive notes were often made to the versos, including stamps and notations of provenance and captions.

In recent decades, as newspapers declined and publications increasingly turned to digital production, the contents of photo morgues have been made available for acquisition by libraries, archives, museums, and, occasionally, private parties such as Churchill Book Collector.

The photographs we will offer show a compelling slice of 20th century newspaper press photography through the prism of an individual who was integral to much of that century’s momentous history. The photographs come from a variety of sources, from standard news agencies to direct from the studios of noted photographers. The hand-applied edits range from mere contrast adjustments to the complete erasure of figures.

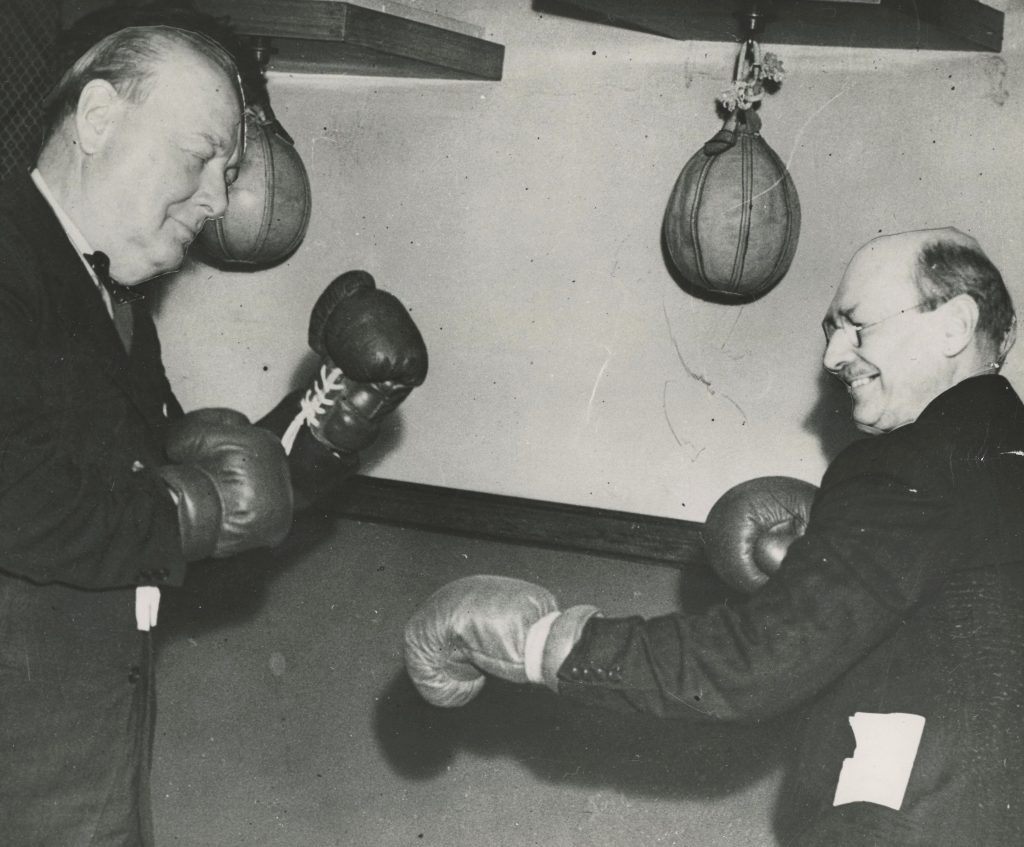

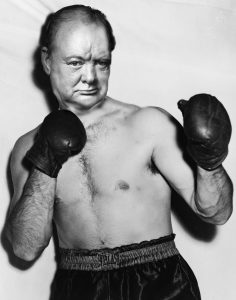

One remarkable photo, of Churchill and Attlee’s faces pasted onto the bodies of two sparring boxers, reminds us that photos mischieviously edited for humor have existed for longer than we might assume.

In this collection of press photographs, we see Churchill as a family man, his arm around Clementine in the midst of the Battle of Britain, or brushing the cheek of his grandchild. We see Churchill as a military leader, inspecting troops and firing guns.

We see Churchill the statesman with world leaders both expected (George VI and FDR) and more unexpected (Nixon and a Nazi leader).

We see Churchill the orator as he gives speeches and radio broadcasts.

And in the photos of Churchill’s final years we are reminded of the inescapable and inexorable toll of physical mortality, which disregards the longevity of words or deeds.

Which brings us full circle to the notion of why a bookseller trades in photographs.

As we have written before, published work has limitations inherent to the very acts of drafting and editing, of expert input, careful consideration, and diligent preparation. Published words, however luminous and illuminating, can find themselves separated from the vitality and immediacy of a moment or perspective.

Photographs are something different. More ephemeral, more candid, more distinctly in and of the moment. Able to impart a vital sense of things that no acclaimed book or carefully crafted speech – however Churchillian in mastery – can quite capture. So even though Churchill left us a wealth of published words, there is more yet to see and to feel from photographs.

At present we plan to release these images for sale in groupings, in roughly reverse chronological order, beginning with the first 60 we have just listed spanning Churchill’s final decade. We are likely to offer the final 100 or so in a dedicated catalogue released concurrent with the 36thAnnual Churchill Conference, to be held in Washington, D.C. 29-31 October 2019.We look forward to sharing with you the incredible wealth of history and photography contained within this archive of original press photographs of Winston. S. Churchill.

Click HERE to browse our entire listed inventory of photographs.

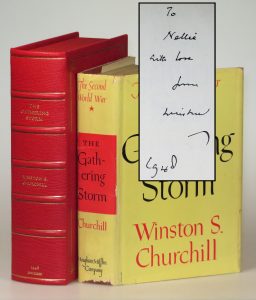

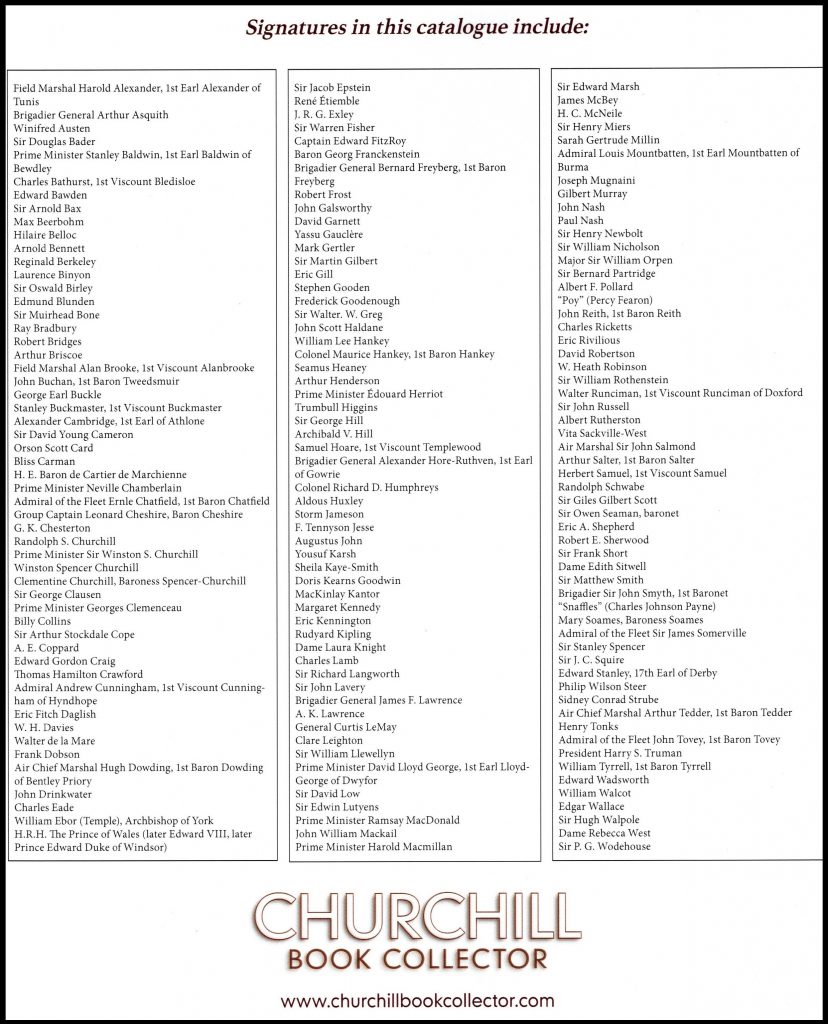

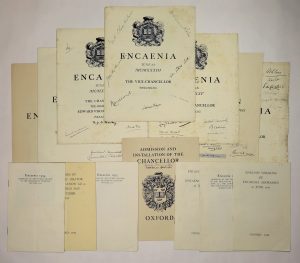

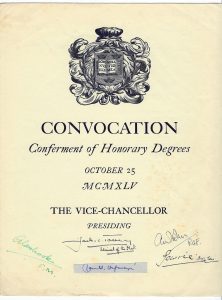

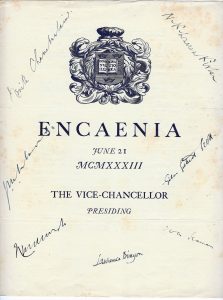

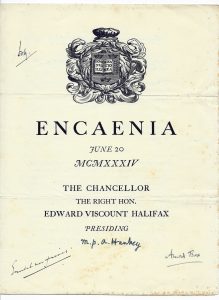

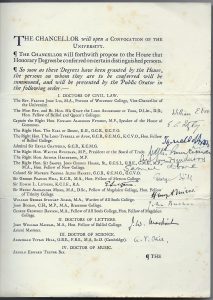

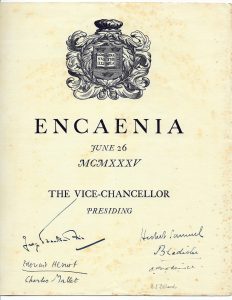

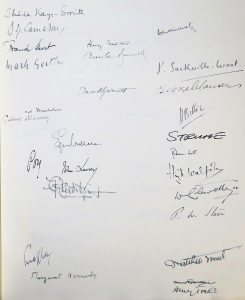

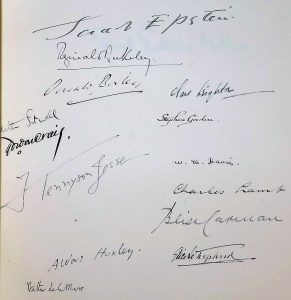

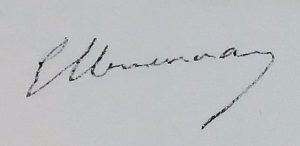

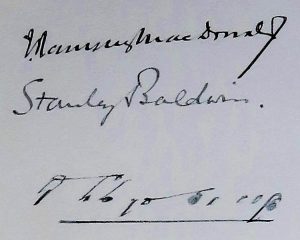

Among the 40 items in our forthcoming catalogue is a collection of Oxford Encaenia program(me)s rendered unique by the signatures of 53 distinguished honorees. The signatures include Prime Ministers Winston Churchill, Neville Chamberlain, and Harold Macmillan, President Harry S. Truman, three Nobel Prize winners, House Speakers and Party Leaders, scholars and war heroes, poets and architects, and such quintessentially British figures as the first Director-General of the BBC, the editor of Punch, and the designer of the London’s iconic red phone booth.

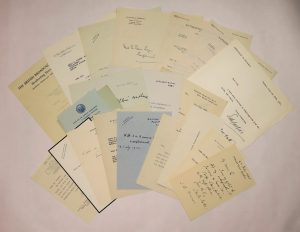

Among the 40 items in our forthcoming catalogue is a collection of Oxford Encaenia program(me)s rendered unique by the signatures of 53 distinguished honorees. The signatures include Prime Ministers Winston Churchill, Neville Chamberlain, and Harold Macmillan, President Harry S. Truman, three Nobel Prize winners, House Speakers and Party Leaders, scholars and war heroes, poets and architects, and such quintessentially British figures as the first Director-General of the BBC, the editor of Punch, and the designer of the London’s iconic red phone booth. These signatures were collected by Lewis Frewer, an Oxford autograph collector whose meticulously catalogued collection of personally acquired signatures of statesmen, sportsmen, and figures of the stage and screen totaled over 2,000 items. This portion of his collection includes 12 signed programs and 35 additional items chiefly comprising letters attesting to the provenance for many of the signatures.

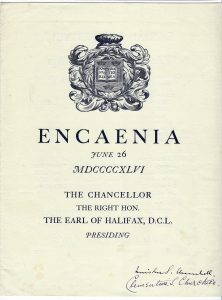

These signatures were collected by Lewis Frewer, an Oxford autograph collector whose meticulously catalogued collection of personally acquired signatures of statesmen, sportsmen, and figures of the stage and screen totaled over 2,000 items. This portion of his collection includes 12 signed programs and 35 additional items chiefly comprising letters attesting to the provenance for many of the signatures. Of course, the figure central to Allied victory, Winston S. Churchill, is also present. However, the honor of Doctor of Civil Law was not placed on the wartime Prime Minister but on his wife, Clementine, whose signature nevertheless appears below her lauded husband and who is referred to in the program as only “Mrs. Churchill”.

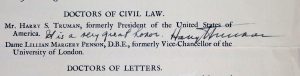

Of course, the figure central to Allied victory, Winston S. Churchill, is also present. However, the honor of Doctor of Civil Law was not placed on the wartime Prime Minister but on his wife, Clementine, whose signature nevertheless appears below her lauded husband and who is referred to in the program as only “Mrs. Churchill”. Immediately after the elections Truman’s name was resubmitted for 1955 and approved. However, Truman would not be able to attend the ceremony until the following year. This again made more trouble for the Foreign Office, as 1956 was an election year, creating a conflict between the embarrassment of delaying the former President’s honor and the consequences of perceived favoritism in American elections. The solution was to include Truman in the 1956 ceremony while making it explicit that he was a holdover from the previous year. Truman’s inscription, that “it is a very great honor”, might be regarded as gracefully acknowledging the political maneuvering required to include him in the Encaenia.

Immediately after the elections Truman’s name was resubmitted for 1955 and approved. However, Truman would not be able to attend the ceremony until the following year. This again made more trouble for the Foreign Office, as 1956 was an election year, creating a conflict between the embarrassment of delaying the former President’s honor and the consequences of perceived favoritism in American elections. The solution was to include Truman in the 1956 ceremony while making it explicit that he was a holdover from the previous year. Truman’s inscription, that “it is a very great honor”, might be regarded as gracefully acknowledging the political maneuvering required to include him in the Encaenia.

Encaenia, June 21, 1933

Encaenia, June 21, 1933

The First World War is often eclipsed by the conflagrations of the latter part of the twentieth century, notably the Second World War and Cold War. But it was the First World War that truly stunned civilization, ushering an age of inconceivable carnage and industrialized brutality. When war came in August 1914, prevailing sentiment held that the conflict would be decisive and short. “You will be home before the leaves have fallen from the trees,” Kaiser Wilhelm assured his troops leaving for the front. More than four extraordinarily bloody years followed, lasting until the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. In his own history of WWI, Winston Churchill wrote: “Overwhelming populations, unlimited resources, measureless sacrifice… could not prevail for fifty months…”

The First World War is often eclipsed by the conflagrations of the latter part of the twentieth century, notably the Second World War and Cold War. But it was the First World War that truly stunned civilization, ushering an age of inconceivable carnage and industrialized brutality. When war came in August 1914, prevailing sentiment held that the conflict would be decisive and short. “You will be home before the leaves have fallen from the trees,” Kaiser Wilhelm assured his troops leaving for the front. More than four extraordinarily bloody years followed, lasting until the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. In his own history of WWI, Winston Churchill wrote: “Overwhelming populations, unlimited resources, measureless sacrifice… could not prevail for fifty months…”

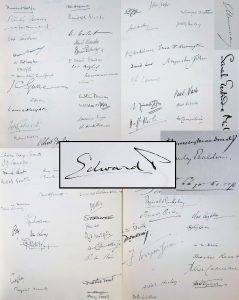

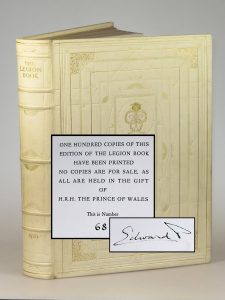

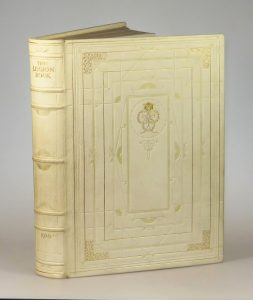

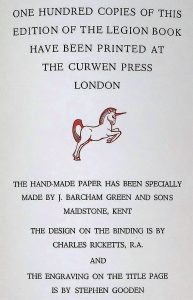

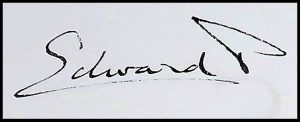

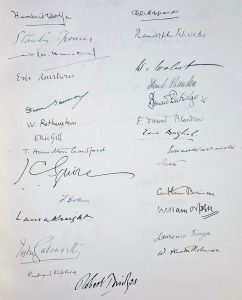

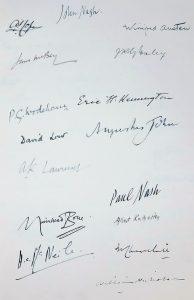

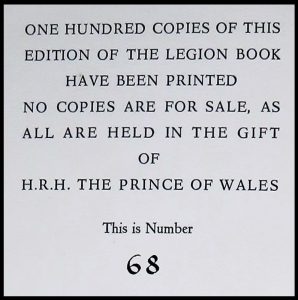

The Legion Book was commissioned by the Legion’s patron, H.R.H. The Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII and, after abdication, the Duke of Windsor). Sale proceeds were dedicated to the Legion. The dozens of contributing artists and writers were among the most talented British subjects in their fields, including Winston Churchill, Rudyard Kipling, P.G. Wodehouse, Aldous Huxley, Vita Sackville-West, G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Augustus John, Eric Kennington, and John Nash. The book was edited by James Humphrey Cotton Minchin (1894-1966), a WWI veteran of the Cameronians and the Royal Flying Corps. Trade editions ran to multiple printings. There was also a 600 copy limited edition. 500 of these were signed by the editor and bound similarly to trade editions. But “the first 100 were reserved for H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, sponsor of the volume, in his gift.”

The Legion Book was commissioned by the Legion’s patron, H.R.H. The Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII and, after abdication, the Duke of Windsor). Sale proceeds were dedicated to the Legion. The dozens of contributing artists and writers were among the most talented British subjects in their fields, including Winston Churchill, Rudyard Kipling, P.G. Wodehouse, Aldous Huxley, Vita Sackville-West, G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Augustus John, Eric Kennington, and John Nash. The book was edited by James Humphrey Cotton Minchin (1894-1966), a WWI veteran of the Cameronians and the Royal Flying Corps. Trade editions ran to multiple printings. There was also a 600 copy limited edition. 500 of these were signed by the editor and bound similarly to trade editions. But “the first 100 were reserved for H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, sponsor of the volume, in his gift.” These hundred were simply magnificent – printed in red and black by The Curwen Press on larger, hand-made paper, profusely illustrated, extravagantly bound in elaborate blind and gilt-tooled white pigskin. Massive volumes, they measure 13 x 10 x 2 inches and weigh 6.6 pounds. Each copy was hand-numbered.

These hundred were simply magnificent – printed in red and black by The Curwen Press on larger, hand-made paper, profusely illustrated, extravagantly bound in elaborate blind and gilt-tooled white pigskin. Massive volumes, they measure 13 x 10 x 2 inches and weigh 6.6 pounds. Each copy was hand-numbered. Winifred Austen

Winifred Austen Laurence Binyon

Laurence Binyon Sir Arthur Cope

Sir Arthur Cope David Garnett

David Garnett Dame Laura Knight

Dame Laura Knight Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray Charles Ricketts

Charles Ricketts Edith Sitwell

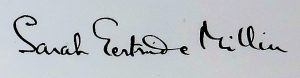

Edith Sitwell We will soon be pleased to offer an unusually fine example, copy “68”, hand-numbered thus on the limitation page. The binding and contents are nearly flawless.

We will soon be pleased to offer an unusually fine example, copy “68”, hand-numbered thus on the limitation page. The binding and contents are nearly flawless. Superlative condition owes to the presence of the original felt-lined cloth clamshell case, with a discreet, inked “No.68” on the upper front cover.

Superlative condition owes to the presence of the original felt-lined cloth clamshell case, with a discreet, inked “No.68” on the upper front cover.

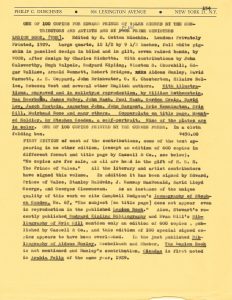

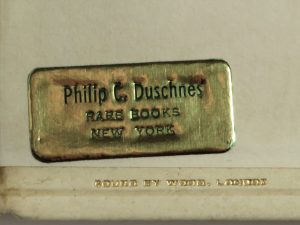

Laid in the case is an original description of this book by noted New York bookseller Philip C. Duschnes, who died in 1970. His tiny gilt sticker is affixed to the lower rear pastedown.

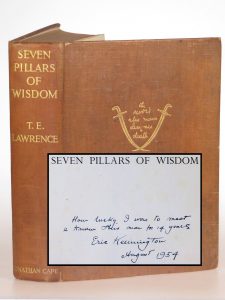

Laid in the case is an original description of this book by noted New York bookseller Philip C. Duschnes, who died in 1970. His tiny gilt sticker is affixed to the lower rear pastedown. Today, a first trade edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdomrendered special by a poignant inscription by Eric Kennington, the man who created thirty-one of the illustrations within its pages. Inked in blue in four lines on the half title, Kennington wrote: “How lucky I was to meet | & know this man for 14 years | Eric Kennington | August 1954”.

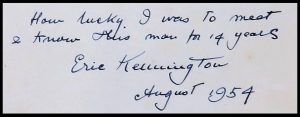

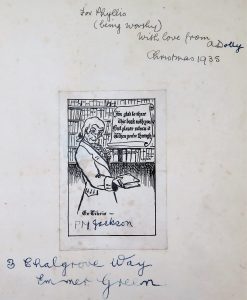

Today, a first trade edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdomrendered special by a poignant inscription by Eric Kennington, the man who created thirty-one of the illustrations within its pages. Inked in blue in four lines on the half title, Kennington wrote: “How lucky I was to meet | & know this man for 14 years | Eric Kennington | August 1954”. A gift inscription “For Phyllis” dated “Christmas 1935” is inked on the front free endpaper above the illustrated book plate of “PM Jackson”.

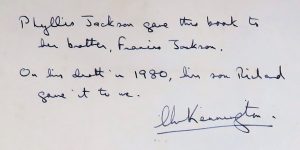

A gift inscription “For Phyllis” dated “Christmas 1935” is inked on the front free endpaper above the illustrated book plate of “PM Jackson”. A five-line inked notation on the front free endpaper verso that appears to be signed by Christopher Kennington (Eric Kennington’s son) reads: “Phyllis Jackson gave this book to | her brother, Francis Jackson. | On his death in 1980, his son Richard | gave it to me.”

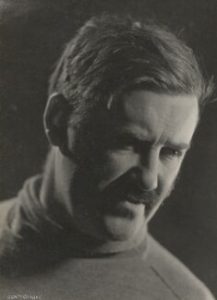

A five-line inked notation on the front free endpaper verso that appears to be signed by Christopher Kennington (Eric Kennington’s son) reads: “Phyllis Jackson gave this book to | her brother, Francis Jackson. | On his death in 1980, his son Richard | gave it to me.” Eric Henri Kennington (1888-1960) was known as a painter, print maker, and sculptor and, most notably, as “a born painter of the nameless heroes of the rank and file” whom he portrayed during both the First and Second World War.

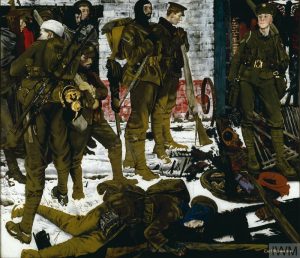

Eric Henri Kennington (1888-1960) was known as a painter, print maker, and sculptor and, most notably, as “a born painter of the nameless heroes of the rank and file” whom he portrayed during both the First and Second World War. Badly wounded on the Western Front in 1915, during his convalescence he produced The Kensingtons at Laventie, a portrait of a group of infantrymen. When exhibited in the spring of 1916 its portrayal of exhausted soldiers created a sensation. Kennington finished the war employed as a war artist by the Ministry of Information. After the war, he met T. E. Lawrence at an exhibition of Kennington’s war art.

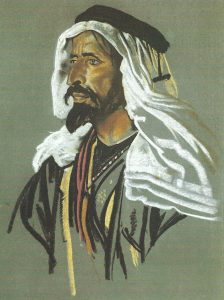

Badly wounded on the Western Front in 1915, during his convalescence he produced The Kensingtons at Laventie, a portrait of a group of infantrymen. When exhibited in the spring of 1916 its portrayal of exhausted soldiers created a sensation. Kennington finished the war employed as a war artist by the Ministry of Information. After the war, he met T. E. Lawrence at an exhibition of Kennington’s war art. In 1921, Kennington traveled to the Middle East with Lawrence where, Lawrence approvingly wrote of his work, “instinctively he drew the men of the desert.” Kennington served as art editor for Lawrence’s legendary 1926 Subscribers’ Edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdomand produced many of the drawings therein.

In 1921, Kennington traveled to the Middle East with Lawrence where, Lawrence approvingly wrote of his work, “instinctively he drew the men of the desert.” Kennington served as art editor for Lawrence’s legendary 1926 Subscribers’ Edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdomand produced many of the drawings therein. That same year he produced a bust of Lawrence – an image of which is the frontispiece of this book. On 15 February 1927, Lawrence wrote to Kennington praising the bust as “magnificent”. Lawrence said “It represents not me, but my top-moments, those few seconds in which I succeed in thinking myself right out of things.” In 1935, Kennington served as one of Lawrence’s pallbearers.

That same year he produced a bust of Lawrence – an image of which is the frontispiece of this book. On 15 February 1927, Lawrence wrote to Kennington praising the bust as “magnificent”. Lawrence said “It represents not me, but my top-moments, those few seconds in which I succeed in thinking myself right out of things.” In 1935, Kennington served as one of Lawrence’s pallbearers. In 1936 his second, memorial bust of Lawrence was installed in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Kennington was again an official war artist for the British government during the Second World War (Ministry of Information and Air Ministry), producing a large number of portraits of individual soldiers in addition to military scenes. Kennington died a member of the Royal Academy six years after writing the inscription in this book.

In 1936 his second, memorial bust of Lawrence was installed in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Kennington was again an official war artist for the British government during the Second World War (Ministry of Information and Air Ministry), producing a large number of portraits of individual soldiers in addition to military scenes. Kennington died a member of the Royal Academy six years after writing the inscription in this book. It was only in the summer of 1935, in the weeks following Lawrence’s death, that the text of the Subscribers’ Edition text was finally published for circulation to the general public in the form of a British first trade edition. This copy inscribed by Kennington is the first printing of this British first trade edition. Condition is good, showing the aesthetic flaws of age and wear, but sound. The khaki cloth binding is square and tight with wear to extremities, overall soiling and staining, and considerable scuffing to the rear cover. The contents are clean with toning to the page edges. A tiny Colchester bookseller sticker is affixed to the lower rear pastedown.

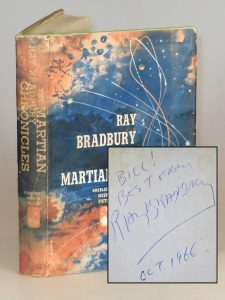

It was only in the summer of 1935, in the weeks following Lawrence’s death, that the text of the Subscribers’ Edition text was finally published for circulation to the general public in the form of a British first trade edition. This copy inscribed by Kennington is the first printing of this British first trade edition. Condition is good, showing the aesthetic flaws of age and wear, but sound. The khaki cloth binding is square and tight with wear to extremities, overall soiling and staining, and considerable scuffing to the rear cover. The contents are clean with toning to the page edges. A tiny Colchester bookseller sticker is affixed to the lower rear pastedown. Look for this and dozens of other signed or inscribed items in our “Extra Ink” catalogue late in 2018!

Look for this and dozens of other signed or inscribed items in our “Extra Ink” catalogue late in 2018!

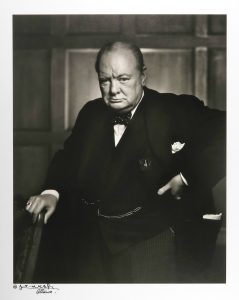

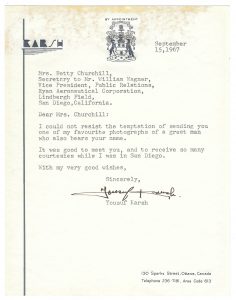

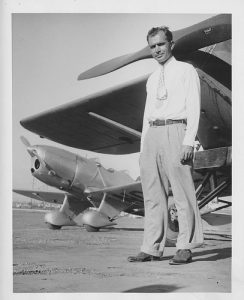

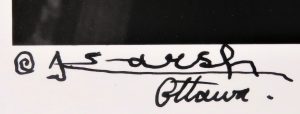

The photo itself is signed by Karsh in black in two lines on the lower left margin of the photo “© Y Karsh | Ottawa.” But in addition to Karsh’s signature, this photo comes with a presentation letter from Karsh typed on his Ottawa studio stationery and signed “Yousuf Karsh.” The letter is dated “September 15, 1967” and addressed: “Mrs. Betty Churchill, Secretary to Mr. William Wagner, Vice President, Public Relations, Ryan Aeronautical Corporation, Lindbergh Field, San Diego, California.”

The photo itself is signed by Karsh in black in two lines on the lower left margin of the photo “© Y Karsh | Ottawa.” But in addition to Karsh’s signature, this photo comes with a presentation letter from Karsh typed on his Ottawa studio stationery and signed “Yousuf Karsh.” The letter is dated “September 15, 1967” and addressed: “Mrs. Betty Churchill, Secretary to Mr. William Wagner, Vice President, Public Relations, Ryan Aeronautical Corporation, Lindbergh Field, San Diego, California.” Tubal Claude Ryan (1898-1982) bought his first airplane, a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny, in San Diego in 1922, and began his aeronautical enterprises by charging for rides. By the late 1920s his aviation ventures included the nation’s first year-round regularly scheduled daily airline passenger service. In 1927, Ryan’s namesake company was tasked with building a single-engine plane that would be called The Spirit of St. Louis for a fellow named Charles Lindbergh.

Tubal Claude Ryan (1898-1982) bought his first airplane, a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny, in San Diego in 1922, and began his aeronautical enterprises by charging for rides. By the late 1920s his aviation ventures included the nation’s first year-round regularly scheduled daily airline passenger service. In 1927, Ryan’s namesake company was tasked with building a single-engine plane that would be called The Spirit of St. Louis for a fellow named Charles Lindbergh. After Lindberg’s historic solo flight, in 1928 Ryan founded The Ryan Aeronautical Corporation. This company, among many accomplishments, built the preeminent trainer aircraft used though the Second World War, the first jet-plus-propeller aircraft for the Navy, and the first successful vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, as well as pioneering remotely piloted vehicles and jet drones, Doppler systems, and lunar landing radar.

After Lindberg’s historic solo flight, in 1928 Ryan founded The Ryan Aeronautical Corporation. This company, among many accomplishments, built the preeminent trainer aircraft used though the Second World War, the first jet-plus-propeller aircraft for the Navy, and the first successful vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, as well as pioneering remotely piloted vehicles and jet drones, Doppler systems, and lunar landing radar. In 1969, just a few years after this photograph was signed and presented by Karsh, Ryan Aeronautical became Teledyne Ryan, a subsidiary of Teledyne, at an acquisition price of $128 million. Teledyne Ryan became, in turn, part of Northrop Grumman in 1999.

In 1969, just a few years after this photograph was signed and presented by Karsh, Ryan Aeronautical became Teledyne Ryan, a subsidiary of Teledyne, at an acquisition price of $128 million. Teledyne Ryan became, in turn, part of Northrop Grumman in 1999. Churchill’s speech of December 26, 1941 to a joint session of the U.S. Congress was sober, resolved, and eloquently defiant, but of course also featured the sparkle of Churchillian wit, which was irrepressible even in the dark hours of the war: “I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way around, I might have got here on my own.” His speech was also an important personal introduction to the elected leaders he needed to embrace the alliance so vital to his nation. A few days later, in his famous “Some chicken, some neck!” speech of December 30 to both houses of the Canadian Parliament, Churchill was characteristically defiant: “When I warned them that Britain would fight alone whatever they did, their generals told their Prime Minister and his divided Cabinet ‘In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken.’ Some chicken; some neck.”

Churchill’s speech of December 26, 1941 to a joint session of the U.S. Congress was sober, resolved, and eloquently defiant, but of course also featured the sparkle of Churchillian wit, which was irrepressible even in the dark hours of the war: “I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way around, I might have got here on my own.” His speech was also an important personal introduction to the elected leaders he needed to embrace the alliance so vital to his nation. A few days later, in his famous “Some chicken, some neck!” speech of December 30 to both houses of the Canadian Parliament, Churchill was characteristically defiant: “When I warned them that Britain would fight alone whatever they did, their generals told their Prime Minister and his divided Cabinet ‘In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken.’ Some chicken; some neck.” Born in Armenian Turkey, Karsh had fled on foot with his family to Syria before immigrating to Canada in 1924 as a refugee. After apprenticing with the celebrity portrait photographer John H. Garo, Karsh moved to Ottawa, where he opened a portrait studio with the intent of photographing “people of consequence.” His breakthrough came in 1936 when he photographed the meeting between U.S. President

Born in Armenian Turkey, Karsh had fled on foot with his family to Syria before immigrating to Canada in 1924 as a refugee. After apprenticing with the celebrity portrait photographer John H. Garo, Karsh moved to Ottawa, where he opened a portrait studio with the intent of photographing “people of consequence.” His breakthrough came in 1936 when he photographed the meeting between U.S. President  Printing date is established by the letter and the fact that Karsh stopped signing his photos with “Ottawa” in the late 1960s. The image verso bears the studio stamp of Karsh’s Ottawa studio reading “COPYRIGHT | the following copyright must be used | © Karsh, Ottawa” as well as a penciled “P of G” notation referring to the image’s inclusion in Karsh’s book Portraits of Greatness(1959).

Printing date is established by the letter and the fact that Karsh stopped signing his photos with “Ottawa” in the late 1960s. The image verso bears the studio stamp of Karsh’s Ottawa studio reading “COPYRIGHT | the following copyright must be used | © Karsh, Ottawa” as well as a penciled “P of G” notation referring to the image’s inclusion in Karsh’s book Portraits of Greatness(1959).

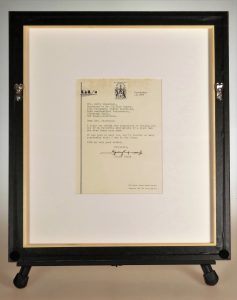

We deliberately chose not to frame in the conventional manner, with the photo matted and framed beside the letter. The photo is simply too striking an image to warrant the aesthetic distraction of the letter right beside it. Instead, we commissioned a custom, double-sided frame using museum quality, archival materials. The solid walnut frame is stained dark black with a thick 8-ply rag board mat for added depth and richness and is glazed with UV filtering acrylic. On the reverse the letter has also been matted and glazed. The framed piece measures 17.375 x 15.375 inches (44.1 x 39 cm).

We deliberately chose not to frame in the conventional manner, with the photo matted and framed beside the letter. The photo is simply too striking an image to warrant the aesthetic distraction of the letter right beside it. Instead, we commissioned a custom, double-sided frame using museum quality, archival materials. The solid walnut frame is stained dark black with a thick 8-ply rag board mat for added depth and richness and is glazed with UV filtering acrylic. On the reverse the letter has also been matted and glazed. The framed piece measures 17.375 x 15.375 inches (44.1 x 39 cm).

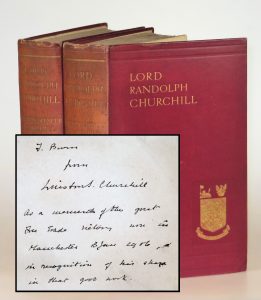

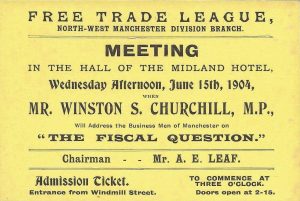

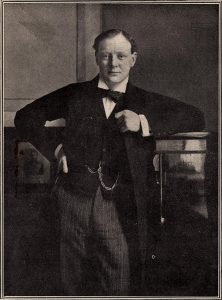

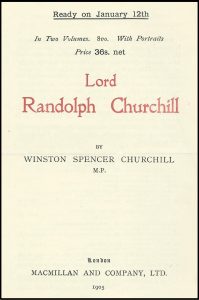

On 31 May 1904 Churchill left his father’s Conservative Party, crossing the aisle to become a Liberal, beginning a dynamic chapter in his political career that saw him champion progressive causes and branded a traitor to his class. On 2 January 1906 Churchill published his two-volume biography of his father. Immediately thereafter, he campaigned for eight days in North-West Manchester, hoping to win his first election as a Liberal.

On 31 May 1904 Churchill left his father’s Conservative Party, crossing the aisle to become a Liberal, beginning a dynamic chapter in his political career that saw him champion progressive causes and branded a traitor to his class. On 2 January 1906 Churchill published his two-volume biography of his father. Immediately thereafter, he campaigned for eight days in North-West Manchester, hoping to win his first election as a Liberal. Churchill’s defection from the Conservative Party was much on the minds of the voters. His father’s history was much on his own mind. To the charge of being a political turncoat, Churchill replied: “I admit I have changed my Party. I don’t deny it. I am proud of it. When I think of all of the labours Lord Randolph Churchill gave to the fortunes of the Conservative Party and the ungrateful way he was treated by them when they obtained the power they would never have had but for him, I am delighted that circumstances have enabled me to break with them while I am still young, and still have the best energies of my life to give to the popular cause.”

Churchill’s defection from the Conservative Party was much on the minds of the voters. His father’s history was much on his own mind. To the charge of being a political turncoat, Churchill replied: “I admit I have changed my Party. I don’t deny it. I am proud of it. When I think of all of the labours Lord Randolph Churchill gave to the fortunes of the Conservative Party and the ungrateful way he was treated by them when they obtained the power they would never have had but for him, I am delighted that circumstances have enabled me to break with them while I am still young, and still have the best energies of my life to give to the popular cause.” North-West Manchester would prove a brief and fraught interlude in Churchill’s six-decade Parliamentary career, his shortest relationship among the five constituencies he ultimately held. In 1908 when Churchill was appointed to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade, custom required that he submit to re-election. His by-election became a test of confidence in the Liberal government. Forced to defend the Government’s policies, targeted by vengeful Conservatives, and hounded on the hustings by Suffragettes, Churchill was narrowly defeated by the Conservative candidate.

North-West Manchester would prove a brief and fraught interlude in Churchill’s six-decade Parliamentary career, his shortest relationship among the five constituencies he ultimately held. In 1908 when Churchill was appointed to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade, custom required that he submit to re-election. His by-election became a test of confidence in the Liberal government. Forced to defend the Government’s policies, targeted by vengeful Conservatives, and hounded on the hustings by Suffragettes, Churchill was narrowly defeated by the Conservative candidate. Nonetheless, the 13 January 1906 election and Churchill’s brief time as M.P. for North-West Manchester made all things possible for him. At 31 years old, “Churchill was now a Junior Minister in a Government furnished with far greater authority than it had expected.” Disraeli’s biographer wrote to congratulate Churchill “both on his book and the beginning of his official career”.

Nonetheless, the 13 January 1906 election and Churchill’s brief time as M.P. for North-West Manchester made all things possible for him. At 31 years old, “Churchill was now a Junior Minister in a Government furnished with far greater authority than it had expected.” Disraeli’s biographer wrote to congratulate Churchill “both on his book and the beginning of his official career”. All this was as yet unseen when he won his first seat as a Liberal in North-West Manchester on 13 January 1906. Nonetheless, we can reasonably speculate that the importance of the victory was not lost upon Churchill. Churchill’s biography of his father had helped place Lord Randolph in historical context. We can also speculate that Churchill’s electoral victory as a Liberal in North-West Manchester helped Churchill put the specter of Lord Randolph’s failed political career behind him. Perhaps all of this was in Churchill’s mind – or perhaps he was simply grateful – when he paused to warmly inscribe this first edition of his newly published book to the man who helped him achieve success. Irrespective, this presentation set testifies to the remarkable convergences of a pivotal moment in the life of both ascending Winstons – the literary and the political.

All this was as yet unseen when he won his first seat as a Liberal in North-West Manchester on 13 January 1906. Nonetheless, we can reasonably speculate that the importance of the victory was not lost upon Churchill. Churchill’s biography of his father had helped place Lord Randolph in historical context. We can also speculate that Churchill’s electoral victory as a Liberal in North-West Manchester helped Churchill put the specter of Lord Randolph’s failed political career behind him. Perhaps all of this was in Churchill’s mind – or perhaps he was simply grateful – when he paused to warmly inscribe this first edition of his newly published book to the man who helped him achieve success. Irrespective, this presentation set testifies to the remarkable convergences of a pivotal moment in the life of both ascending Winstons – the literary and the political.