When I hear contemporary politicians invoke Churchill, I usually feel like I’m watching King Louie, the Orangutan who wants to be a man, sing “I wanna be like you” in the 1967 Disney version of The Jungle Book.

“You!” sings King Louie,

“I wanna be like you

I wanna talk like you

Walk like you, too”

Yeah. Not so much.

IF you happen to draw a comparison between King Louis and another loud, big-headed, oddly orange, wanna-be-king with impulse control issues and destructive inclinations, well, that’s up to you. I refer you to another Disney movie. Cinderella. If the shoe fits… But I digress.

“I’m tired of monkeyin’ around!”

Sure, there’s a lot of ways in which most of those who self-flatteringly invoke Churchill fall short. Intelligence. Eloquence, Historical perspective. Foresight. Principle. Conviction. Courage. General capability. But, to me, none of these are the biggest shortcomings of the chorus of King Louie/wannabe Churchills. In my book, here’s the most important and most regrettable thing the Louies typically lack – a presumption of shared purpose and the primacy of decency.

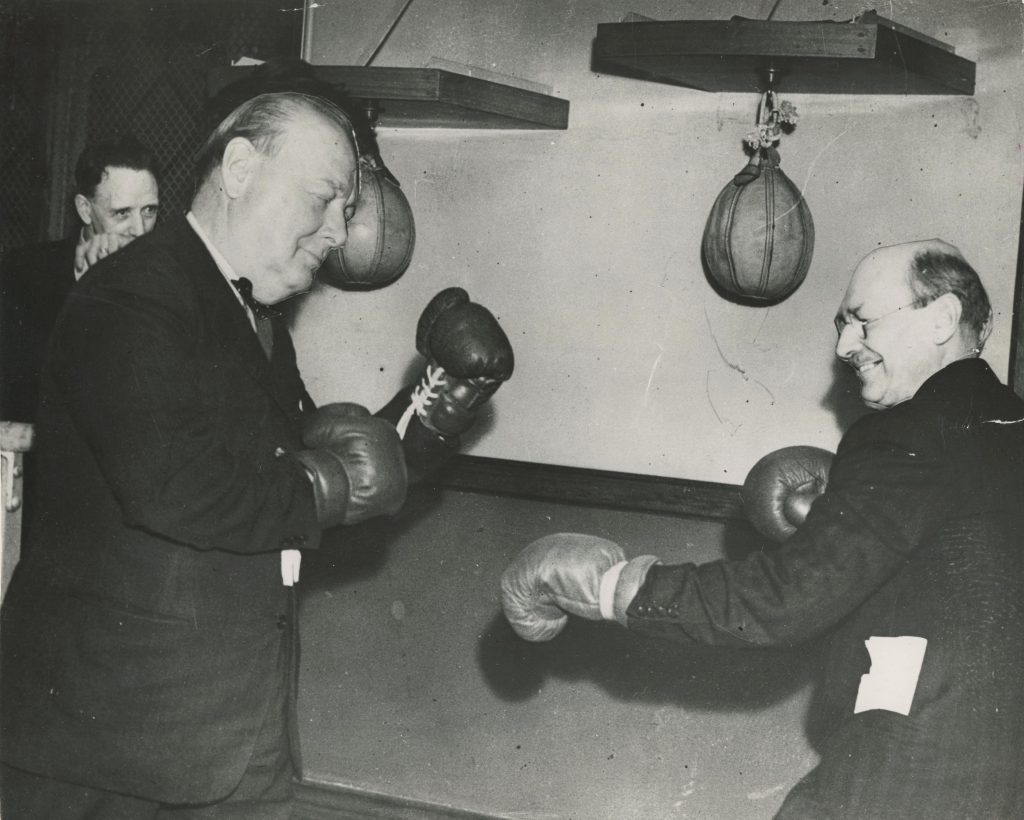

Churchill could be fiercely partisan and relentless in pursuit of a policy or cause. And he was a true combatant by nature, whether on the battlefield, at the rostrum, on the backbenches, in Cabinet, leading a Government, or leading the Opposition. But Churchill did not confuse mere opponents with actual enemies. He regarded sincerity of convictions that he did not share. He was able to pursue cooperation in greater cause over petty conflict and momentary aggrandization. He was able to disagree without demonizing.

And, critically, he was not the only one. We were reminded of this recently by “Manny” Shinwell. Or, more accurately, by – of course – a book inscribed to him.

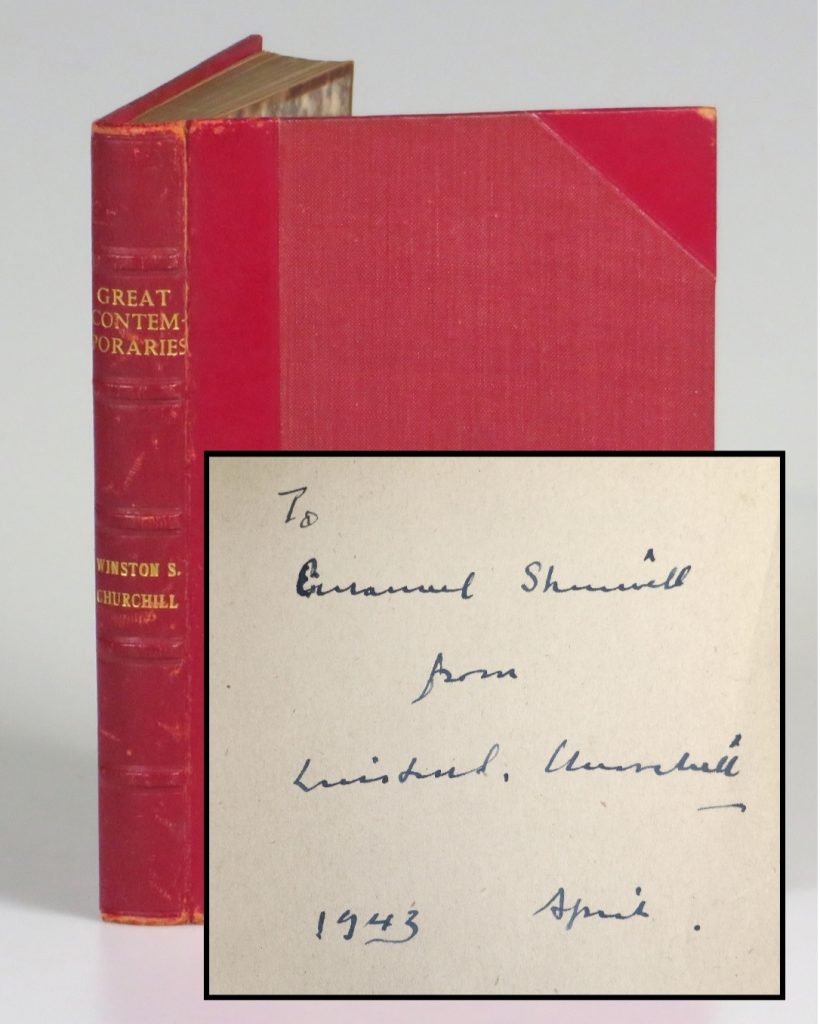

The book in question (found HERE) is Great Contemporaries, Churchill’s famous collection of character sketches, first published in 1937. At the time Churchill had been out of power and out of favor, frequently at odds with both his own party leadership and prevailing public sentiment.

But, in April 1943, Churchill was wartime Prime Minister. This finely bound presentation copy is a wartime reprint inscribed to “one of Churchill’s most persistent Labour Party critics.” Inked in blue in five lines in blue on the blank recto preceding the half title, the inscription reads “To | Emanuel Shinwell | from | Winston S. Churchill | 1943 April.”

A barbed gift?

In April 1943, the British were on the cusp of their first decisive Second World War victory over Hitler’s Germany, and by mid-May would declare “One Continent Redeemed” when Axis forces were expelled from North Africa. In the House of Commons, Emanuel Shinwell, the Member for Seaham Harbour, was apparently feeling less than celebratory, leaning into his role as a leading Parliamentary critic of Churchill’s Government.

Let’s not sugar-coat it. Churchill and Shinwell disagreed strongly, frequently, and were often unstinting in their criticism. A review of the House of Commons records for April 1943 – the month Churchill inscribed this book for Shinwell – indicates that in that month alone Shinwell personally questioned Churchill directly in the House regarding U-Boat losses, wartime suspension of elections, and compensation for ministers. That same month, Shinwell also questioned various ministers of Churchill’s Government regarding post-war planning, property rented by the Royal Air Force, Armed forces, civilian, and old age pensions, operations in Burma, and pay for Army chaplains. And that was just April. (Hansard)

We cannot know precisely what precipitated the gift of this inscribed volume, but it does seem plausible that Churchill may have presented this particular title – Great Contemporaries – with a sense of barbed irony to one of his most vigorous and persistent backbench critics. Another irony is that Churchill might have eventually chosen to include Shinwell’s own profile in this book.

Two pugnacious personalities

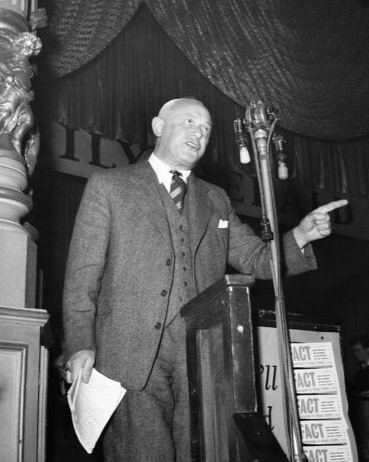

First elected to Parliament in 1922, Emanuel Shinwell, Baron Shinwell (1884-1986) was – not unlike Churchill himself – “a major personality over sixty years” and “always a pugnacious member of parliament” as a vocal and influential member of the Labour Party. (ODNB)

In 1935, two years before Great Contemporaries was first published, Shinwell had turned on and defeated former Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. Not unlike Churchill, Shinwell would spend his long career at turns vexing and serving – sometimes both at once – the leadership of his own party. Like Churchill, he was guided by a strong sense of what was right, and what was not, and of greater priorities than politics or political party.

Pugnacity was literal as well as electoral for Shinwell, who in 1938 actually struck a Conservative member of Parliament – a former naval boxing champion. During the Second World War, “Shinwell was a vigorous, though always patriotic, critic of Winston Churchill’s coalition government.” (ODNB) Hence it is plausible to sense some cheek and irony in Churchill inscribing Great Contemporaries to Shinwell in 1943, even as Shinwell was regularly assailing Churchill and his Government in the House of Commons.

Kinship even in fierce opposition

But however fierce and occasionally sharp their political battles, in the placement of country before party Shinwell and Churchill shared a kinship. During the Normandy invasion in early June 1944, Shinwell wrote a note to Churchill: “I should like you to know that at this time, when the thoughts of all of us are turned on grave events, I and others, whose views do not always accord with Government policy, are with you and your colleagues to a man.” (Letter of 8 June 1944, quoted in Gilbert, Vol. VII, p.800)

As for Shinwell’s criticism, Churchill had ample opportunity to return the favor. Churchill’s government fell to Labour in the General Election of July 1945. Shinwell served in Prime Minister Clement Attlee’s Government, eventually becoming Secretary of State for War in October 1947 and Minister of Defence in February 1950. Shinwell thereby fell squarely in Churchill’s own crosshairs, given Churchill’s extensive experience as wartime leader, architect of the Second World War, and stints as First Lord of the Admiralty (in two different world wars), Minister of Munitions, Secretary of State for War, Secretary of State for Air, and Minister of Defence (ultimately thrice).

You can kick me in the Shin(well) and I’ll still respect you…

Shinwell left office after Churchill’s Conservatives regained a majority in late October 1951, returning Churchill to the premiership. On 6 December 1951, Churchill asked the indulgence of the House in order to speak in praise of Shinwell: “We have our party battles and bitterness… but I have always felt and have always testified.. to the Right Honourable Gentleman’s sterling patriotism and to the fact that his heart is in the right place where the life and strength of our country are concerned… I am so glad to be able to say tonight… that the spirit which has animated the Right Honourable Gentleman in the main discharge of his great duties was one which has, in peace as well as in war, added to the strength and security of our country.”

David Hunt, Churchill’s Private Secretary who had accompanied the Prime Minister to the Commons, recalled that “The House was stirred” and in the car on the way back to Number 10 Churchill reflected on his comments. … there’s a lot of good in Shinwell and I’m glad I took the chance of saying something about him.” Churchill’s fellow Conservatives were not so glad – “For the next week and more, letters of complaint continued to arrive… Churchill was robustly impenitent, and the more that people protested the more certain he felt that he had spoken well.” (Gilbert, Vol. VIII, pp.667-8)

The two men continued to disagree with frequency and vigor throughout Churchill’s second and final premiership. But in July of 1964, the day after Churchill went to the House of Commons for the last time, Shinwell was among a small group of House leaders and elders who called on Churchill at his Hyde Park Gate home to present him with a Resolution of the House of Commons conveying “unbounded admiration and gratitude for his services to Parliament, to the nation and to the world…” (Gilbert, Vol. VIII, p.1354-4)

Shinwell’s own career was far from over, and justly recognized in his own twilight. By the time of his hundredth birthday, which was celebrated in the House of Lords in 1984, Shinwell was “a legendary figure.” Perhaps even, had Churchill had opportunity to retrospectively revise and expand his book, a “Great Contemporary”.

“What I desire is man’s red fire”

Alas, greatness is elusive, and certainly cannot be conferred by appropriation and false equivalence.

“I wanna be a man…

What I desire is man’s red fire

To make my dream come true…

Give me the power of man’s red flower

So I can be like you.”

So sings The Jungle Book’s King Louie (voiced by the incomparable Louis Prima). To make himself more of a “man”, and to enforce his dominion over his unruly kingdom of monkeys, this primate populist wants fire. Poor Louie does not understand that power without purpose and some sense of propriety will not make a man of an ape.

Neither does aping Churchill’s stature without regarding his character.

It is, and has always been, a proverbial jungle out there. There’s nothing new about politics being a rough and tumble affair. There’s nothing special – now or in the past – about vigorous disagreement, scheming and maneuvering, and even saying profoundly unflattering things about politicians in a different camp than your own. Likewise, there is nothing new about self-aggrandizing unworthies trying to elevate themselves by association with their betters.

No one appointed me keeper of Churchill’s reputation. I am not empowered to adjudicate invocation of Churchill’s life and legacy. But there is something cartoonishly clumsy and not the least bit entertaining about watching vaunting pretenders try to rally the rabble to them by invoking Churchill. It would seem more fitting – and better serve the public good that so animated both Manny Shinwell and Winston Churchill – if Churchill were invoked less for flagrant self-justification and more for courageous conciliation and cooperation.

Cheers!