We have just listed a rather remarkable artefact of British colonial presence in India. Mammoth in every sense, this is the 1847, two-volume, first edition of George Everest’s account of his epic survey of the Indian subcontinent. Everest’s survey is the reason why the world’s tallest peak, Mount Everest, was named for this British geodesist and military engineer.

We have just listed a rather remarkable artefact of British colonial presence in India. Mammoth in every sense, this is the 1847, two-volume, first edition of George Everest’s account of his epic survey of the Indian subcontinent. Everest’s survey is the reason why the world’s tallest peak, Mount Everest, was named for this British geodesist and military engineer.

This elaborate and rare set is a presentation copy in the original binding from the author to the Royal Society of Edinburgh at the behest of the Directors of the East India Company.

Each volume is inscribed on the front free endpaper: “Presented by order of the Court of Directors | of the Hon’ble E. I. Company of Great Britain | to the Royal Society of Edinburgh | By the Author”.

Sir George Everest (1790-1866) joined the East India Company as a cadet and sailed for India in 1806. Engineering successes and proficiency in mathematics and astronomy led to his being appointed chief assistant to the great trigonometrical survey of India in 1817. This survey, dauntingly ambitious on an imperial scale, began in 1802 and “was of international geodetic importance because of its part in determining the figure of the earth.” Everest’s task was to complete the arc that had begun at the southern tip of India, work which he continued as superintendent after the 1823 death of William Lambton, his predecessor.

Sir George Everest (1790-1866) joined the East India Company as a cadet and sailed for India in 1806. Engineering successes and proficiency in mathematics and astronomy led to his being appointed chief assistant to the great trigonometrical survey of India in 1817. This survey, dauntingly ambitious on an imperial scale, began in 1802 and “was of international geodetic importance because of its part in determining the figure of the earth.” Everest’s task was to complete the arc that had begun at the southern tip of India, work which he continued as superintendent after the 1823 death of William Lambton, his predecessor.

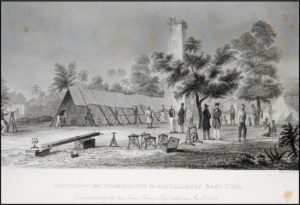

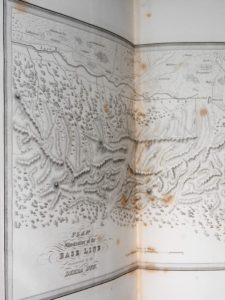

Triangulation surveys were based on carefully measured baselines and a series of angles. The initial baseline was measured with great accuracy – a daunting technical and logistical feat in colonial India – since the accuracy of the subsequent survey was critically dependent upon it. The text volume’s frontispiece engraving is of the “Termination of the Calcutta Base Line”. Of note, a significant part of Everest’s work was highly technical in nature and he did not just rely on and reward British ingenuity; Everest “promoted to positions of considerable importance local staff such as the computer Radhanath Sickdhar and the instrument maker Saiyid Mir Mohsin Hussain.” (ODNB)

Triangulation surveys were based on carefully measured baselines and a series of angles. The initial baseline was measured with great accuracy – a daunting technical and logistical feat in colonial India – since the accuracy of the subsequent survey was critically dependent upon it. The text volume’s frontispiece engraving is of the “Termination of the Calcutta Base Line”. Of note, a significant part of Everest’s work was highly technical in nature and he did not just rely on and reward British ingenuity; Everest “promoted to positions of considerable importance local staff such as the computer Radhanath Sickdhar and the instrument maker Saiyid Mir Mohsin Hussain.” (ODNB)

Everest spent the next two decades intensely committed to the trigonometrical survey. He directly participated in field work, “even though half paralysed from the effects of fever and rheumatism.” When he became too ill to work in the field, Everest returned to England to win support of the East India Company for project completion, to promote scientific interest, and secure improvements in measurement instruments and methods. Everest returned to India in 1830 not only as an elected fellow of the Royal Society and superintendent of the trigonometric survey, but also as surveyor-general of India. Despite further bouts of sickness, “he was able to see the work through to completion in 1841 under Andrew Scott Waugh by which time an arc of more than 21 degrees in length had been measured from Cape Comorin to the northern border of British India.” (ODNB)

In late 1843, Everest retired and returned to England. His 1847 publication of An Account of the Measurement of Two Sections of the Meridional Arc of India earned Everest the medal of the Royal Astronomical Society as well as election as an honorary member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal and fellow of the Royal Asiatic and Royal Geographical societies. In 1856, Everest’s name was given by his successor in India, Andrew Waugh, to Peak XV in the Himalayas, the highest summit in the world at 29,029 feet.

Everest’s two-volume work is a magnificently detailed and elaborate publication, rarely seen on the word market and particularly scarce thus – an author’s presentation copy in the original publisher’s bindings.

The handsome original dark blue cloth bindings measure nearly 13 x 10.25 inches, with gilt spine print, blind ruled spine compartments, and blind ruled front cover borders with blind stamped floral motif at corners and center within. The contents are extensively illustrated.

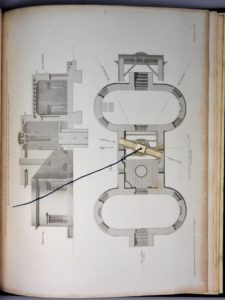

The text volume includes an engraved frontispiece and two plates, illustrations (one with volvelle), and tables (several folding). The Engravings volume includes thirty-two engraved plates, one plate with volvelle, one double-page map, and two enormous folding plan sections. The lower title page of the Engravings volume bears the oval ink stamp of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. We are pleased to offer this magnificent set for sale, HERE.

The text volume includes an engraved frontispiece and two plates, illustrations (one with volvelle), and tables (several folding). The Engravings volume includes thirty-two engraved plates, one plate with volvelle, one double-page map, and two enormous folding plan sections. The lower title page of the Engravings volume bears the oval ink stamp of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. We are pleased to offer this magnificent set for sale, HERE.

As a young cavalry officer and war correspondent serving on the northwest Indian frontier at the end of Queen Victoria’s reign, future British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill mused “…we wonder whether the traveller shall some day inspect, with unconcerned composure, the few scraps of stone and iron which may indicate the British occupation of India…” (The Story of the Malakand Field Force, 1898, p.139) Everest’s “great vision was to calculate the figure of the earth, comparing his great arc with arcs in higher latitude…” His figure was soon superseded and twentieth century satellite technology has completely changed the method of calculating the figure of the earth. What endures is Everest’s importance “as a man of vision who with immense determination carried out his plan to the limits of precision then possible… and whose achievement was of great importance to contemporary geodesy and to the accurate surveying of India.” (ODNB)

As a young cavalry officer and war correspondent serving on the northwest Indian frontier at the end of Queen Victoria’s reign, future British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill mused “…we wonder whether the traveller shall some day inspect, with unconcerned composure, the few scraps of stone and iron which may indicate the British occupation of India…” (The Story of the Malakand Field Force, 1898, p.139) Everest’s “great vision was to calculate the figure of the earth, comparing his great arc with arcs in higher latitude…” His figure was soon superseded and twentieth century satellite technology has completely changed the method of calculating the figure of the earth. What endures is Everest’s importance “as a man of vision who with immense determination carried out his plan to the limits of precision then possible… and whose achievement was of great importance to contemporary geodesy and to the accurate surveying of India.” (ODNB)

Everest’s name, affixed to the world’s tallest peak – a summit synonymous with both alluring mystique and towering ambition – testifies to the place the Indian subcontinent held in British imagination, ambition, and invention and to an enduring influence greater than any “few scraps of stone and iron.”

One thought on “Naming the world’s tallest mountain”