English is a language rich in vocabulary, some words having almost peculiar specificity. Among the most peculiar and specific known to this bookseller is “Encaenia”.

Perhaps you know the word. I confess that “Encaenia” did not join my own vocabulary until this year. Apropos, my Oxford English Dictionary tells me that it is “The annual commemoration of founders and benefactors at Oxford University”.

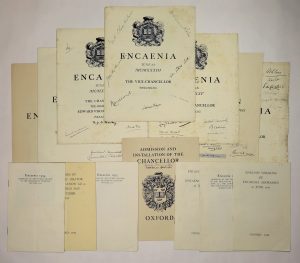

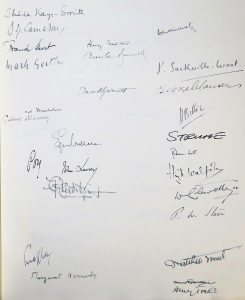

Among the 40 items in our forthcoming catalogue is a collection of Oxford Encaenia program(me)s rendered unique by the signatures of 53 distinguished honorees. The signatures include Prime Ministers Winston Churchill, Neville Chamberlain, and Harold Macmillan, President Harry S. Truman, three Nobel Prize winners, House Speakers and Party Leaders, scholars and war heroes, poets and architects, and such quintessentially British figures as the first Director-General of the BBC, the editor of Punch, and the designer of the London’s iconic red phone booth.

Among the 40 items in our forthcoming catalogue is a collection of Oxford Encaenia program(me)s rendered unique by the signatures of 53 distinguished honorees. The signatures include Prime Ministers Winston Churchill, Neville Chamberlain, and Harold Macmillan, President Harry S. Truman, three Nobel Prize winners, House Speakers and Party Leaders, scholars and war heroes, poets and architects, and such quintessentially British figures as the first Director-General of the BBC, the editor of Punch, and the designer of the London’s iconic red phone booth.

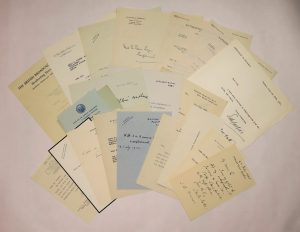

These signatures were collected by Lewis Frewer, an Oxford autograph collector whose meticulously catalogued collection of personally acquired signatures of statesmen, sportsmen, and figures of the stage and screen totaled over 2,000 items. This portion of his collection includes 12 signed programs and 35 additional items chiefly comprising letters attesting to the provenance for many of the signatures.

These signatures were collected by Lewis Frewer, an Oxford autograph collector whose meticulously catalogued collection of personally acquired signatures of statesmen, sportsmen, and figures of the stage and screen totaled over 2,000 items. This portion of his collection includes 12 signed programs and 35 additional items chiefly comprising letters attesting to the provenance for many of the signatures.

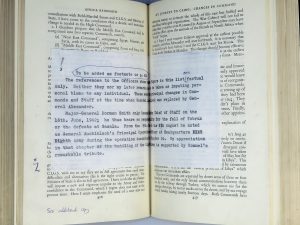

As you might expect, the condition of the items varies. Programs handled by a limited number of people, such as those signed by the Churchills and Truman, are in very good condition, bright and clean with minimal wear to the extremities. Others, such as the 22 June 1932 program, were clearly been sent back and forth through the mail in the process of collecting multiple signatures, and hence bear fold lines, attempted repairs, tears, and visible wear.

The Encaenia ceremony at Oxford has existed since the 16thcentury as a means of conferring honor upon, and obtaining favor from, the powerful and influential in the form of honorary degrees. This means of using honorary degrees to create alliances extended from the academic realm to the British Government by the 1930s when the Foreign Office reportedly came to regard the honor as a diplomatic tool and began to directly intervene in the selection of honorees. Reflecting this practice, in this collection are the signatures – all collected in the years leading up to WWII – of foreign dignitaries such as Austrian Minister Baron Georg Franckenstein, French Prime Minister Édouard Herriot, and Belgian diplomat H. E. Baron de Cartier. This level of political calculation was interestingly juxtaposed with the infamous 1933 Oxford Union resolution stating that “this house will under no circumstances fight for its King and Country”, a resolution denounced by Winston Churchill as an “abject, squalid, shameless avowal”.

The “King and Country” resolution aside, in the first half of the 20thcentury, the honorary degrees awarded largely reflected the contributions of British and Allied leaders in the two World Wars, with nearly half of the honorees in 1946 being military figures. Military heroes present here include Admiral of the Fleet Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope, who was ranked “with the greatest of British admirals”, Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding, who was credited with a crucial role in winning the Battle of Britain, Lieutenant General Lord Bernard Freyberg, whose lengthy military career which spanned beach landings at Gallipoli to the Battle of Greece prompted Churchill to nickname him “the Salamander” for his ability to pass unharmed through the fire, and Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke, the chief military advisor to Churchill.

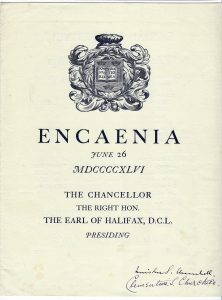

Of course, the figure central to Allied victory, Winston S. Churchill, is also present. However, the honor of Doctor of Civil Law was not placed on the wartime Prime Minister but on his wife, Clementine, whose signature nevertheless appears below her lauded husband and who is referred to in the program as only “Mrs. Churchill”.

Of course, the figure central to Allied victory, Winston S. Churchill, is also present. However, the honor of Doctor of Civil Law was not placed on the wartime Prime Minister but on his wife, Clementine, whose signature nevertheless appears below her lauded husband and who is referred to in the program as only “Mrs. Churchill”.

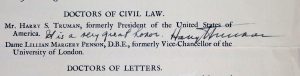

President Harry S. Truman’s inclusion in the 1956 Encaenia was fraught with political controversies. In 1952 Oxford honored Dean Acheson, the US Secretary of State under Truman. Ostensibly, this was a politically safe pick. However, 1952 was an election year, one tainted with anti-communist Cold War rhetoric. After Senator Joseph McCarthy attacked Dean Acheson as soft on communism, Oxford’s decision seemed a miscalculation and was perceived by some as a gesture of support for the foreign policies of the Democratic Party. Two years later Oxford’s Vice-Chancellor proposed Truman’s nomination to Foreign Secretary Antony Eden, whose response was an explicit “no” as the US midterm elections were approaching and the nomination of another prominent Democrat might lend the appearance of intervention. There was additionally some discomfort at awarding an honorary degree to the individual who had given the order for the first atomic bomb to be dropped.

Immediately after the elections Truman’s name was resubmitted for 1955 and approved. However, Truman would not be able to attend the ceremony until the following year. This again made more trouble for the Foreign Office, as 1956 was an election year, creating a conflict between the embarrassment of delaying the former President’s honor and the consequences of perceived favoritism in American elections. The solution was to include Truman in the 1956 ceremony while making it explicit that he was a holdover from the previous year. Truman’s inscription, that “it is a very great honor”, might be regarded as gracefully acknowledging the political maneuvering required to include him in the Encaenia.

Immediately after the elections Truman’s name was resubmitted for 1955 and approved. However, Truman would not be able to attend the ceremony until the following year. This again made more trouble for the Foreign Office, as 1956 was an election year, creating a conflict between the embarrassment of delaying the former President’s honor and the consequences of perceived favoritism in American elections. The solution was to include Truman in the 1956 ceremony while making it explicit that he was a holdover from the previous year. Truman’s inscription, that “it is a very great honor”, might be regarded as gracefully acknowledging the political maneuvering required to include him in the Encaenia.

Below you’ll find a full list of Encaenia and signatures, as well as additional images.

Cheers!

Churchill Book Collector

_______________________________________________________________________

Our collection of Encaenia and the signatures therein include the following:

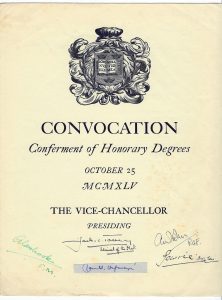

Convocation, Conferment of Honorary Degrees, October 25, 1945

Convocation, Conferment of Honorary Degrees, October 25, 1945

Field Marshal the Lord Alanbrooke

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Jack Tovey

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Tedder

Alexander Hore-Ruthven, First Earl of Gowrie

Unknown

English Versions of Encaenia Addresses, June 26, 1946

Admiral of the Fleet Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Somerville

Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding

Encaenia, June 22, 1932

the Earl of Athalone, Governor General South Africa and of Canada

Sir Arthur Salter, politician

E. Baron de Cartier, Belgian diplomat

Sir John Russell, British Ambassador

George Earl Buckle, writer, editor of the Times

Walter Wilson Greg, Shakespeare scholar

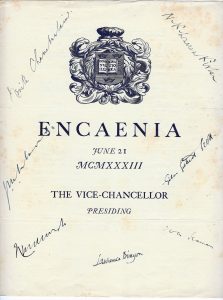

Encaenia, June 21, 1933

Encaenia, June 21, 1933

Front Cover:

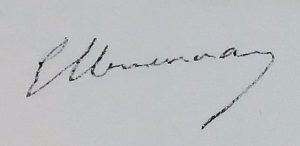

Neville Chamberlain, Prime Minister

Sir John Maitland Salmond, Marshal of the Royal Air Force

Laurence Binyon, English poet

Sir Owen Seaman, editor of Punch

Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, architect, designer of the red phone box

Sir Warren Fisher, Head of the Home Civil Service

Frederick Craufurd Goodenough, chairman of Barclays Bank

Rear cover:

Viscount Buckmaster, Lord Chancellor

John Scott Haldane, physiologist

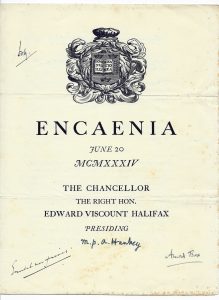

Encaenia, June 20, 1934

Encaenia, June 20, 1934

Cover:

Arnold Bax, composer

Colonel Sir Maurice Paschal Alers Hankey, Cabinet Secretary

Edward Stanley, the 19thEarl of Derby

Admiral Sir Ernle Chatfield

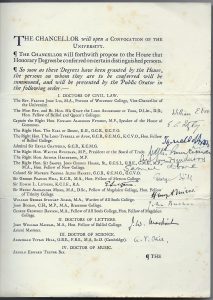

Interior:

The Archbishop of York, William Ebor

Captain Edward Algernon Fitzroy, M.P., Speaker of the House of Commons

Lord Tyrrell of Avon

Walter Runciman, M.P., President of the Board of Trade

Arthur Henderson, M.P., Nobel Peace Prize 1934

Sir Samuel John Gurney Hoare, Secretary of State for Air

Sir George Francis Hill, director of the British Museum

Sir Edwin L. Lutyens, British architect

Sir Henry Alexander Miers, mineralogist

John Buchan, Governor General of Canada, author of The Thirty-Nine Steps

John William Mackail, writer

Archibald Vivian Hill, Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1922

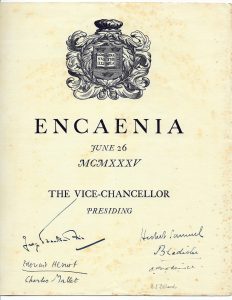

Encaenia, June 26, 1935

Baron Georg Franckenstein, Austrian Minister to the Court of St. James

Albert Frederick Pollard, Tudor historian

Herbert Samuel, Home Secretary, Leader of the Liberal Party

Édouard Herriot, Prime Minister of France

Sir Charles Edward Mallet, historian, Financial Secretary to the War Office

Viscount Bledisloe of Sydney, Gevernor-General of New Zealand

Sir John Charles Walsham Reith, First Director-General of the BBC

Speeches by the Public Orator, October 25, 1945

Lt. Gen. Sir Bernard Freyberg, Victoria Cross, dubbed by Churchill “the Salamander”

Encaenia, June 26, 1946

Winston S. Churchill

Clementine Churchill

English Versions of Encaenia Addresses, June 26, 1946

Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, First Sea Lord, Governor-General of India

Encaenia, June 20, 1956

Harry S. Truman “It is a very great honor. Harry Truman”

Admission and Installation of the Chancellor, April 30, 1960

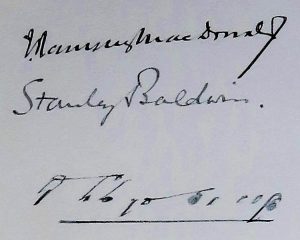

Harold Macmillan, Prime Minister

Encaenia, June 27, 1984

Group Captain Leonard Cheshire (with tipped-in letter), Victoria Cross, philanthropist

The First World War is often eclipsed by the conflagrations of the latter part of the twentieth century, notably the Second World War and Cold War. But it was the First World War that truly stunned civilization, ushering an age of inconceivable carnage and industrialized brutality. When war came in August 1914, prevailing sentiment held that the conflict would be decisive and short. “You will be home before the leaves have fallen from the trees,” Kaiser Wilhelm assured his troops leaving for the front. More than four extraordinarily bloody years followed, lasting until the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. In his own history of WWI, Winston Churchill wrote: “Overwhelming populations, unlimited resources, measureless sacrifice… could not prevail for fifty months…”

The First World War is often eclipsed by the conflagrations of the latter part of the twentieth century, notably the Second World War and Cold War. But it was the First World War that truly stunned civilization, ushering an age of inconceivable carnage and industrialized brutality. When war came in August 1914, prevailing sentiment held that the conflict would be decisive and short. “You will be home before the leaves have fallen from the trees,” Kaiser Wilhelm assured his troops leaving for the front. More than four extraordinarily bloody years followed, lasting until the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. In his own history of WWI, Winston Churchill wrote: “Overwhelming populations, unlimited resources, measureless sacrifice… could not prevail for fifty months…”

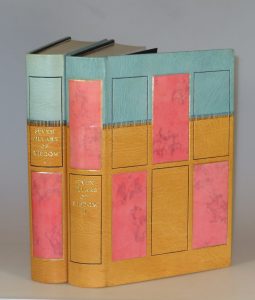

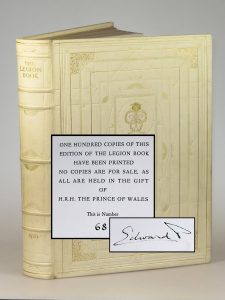

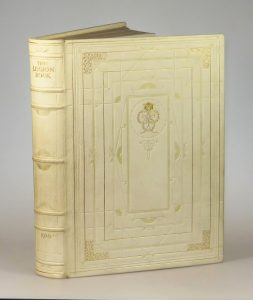

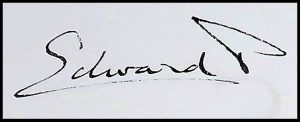

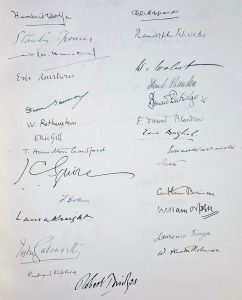

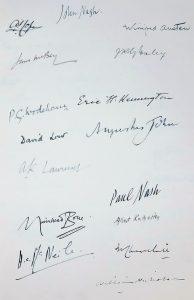

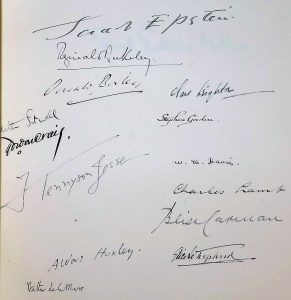

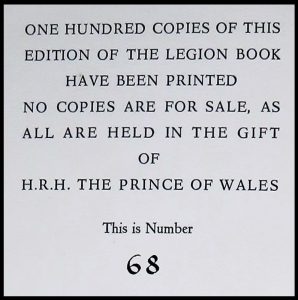

The Legion Book was commissioned by the Legion’s patron, H.R.H. The Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII and, after abdication, the Duke of Windsor). Sale proceeds were dedicated to the Legion. The dozens of contributing artists and writers were among the most talented British subjects in their fields, including Winston Churchill, Rudyard Kipling, P.G. Wodehouse, Aldous Huxley, Vita Sackville-West, G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Augustus John, Eric Kennington, and John Nash. The book was edited by James Humphrey Cotton Minchin (1894-1966), a WWI veteran of the Cameronians and the Royal Flying Corps. Trade editions ran to multiple printings. There was also a 600 copy limited edition. 500 of these were signed by the editor and bound similarly to trade editions. But “the first 100 were reserved for H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, sponsor of the volume, in his gift.”

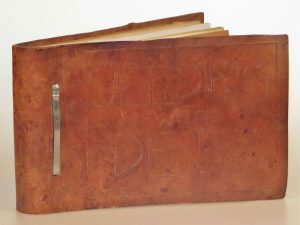

The Legion Book was commissioned by the Legion’s patron, H.R.H. The Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII and, after abdication, the Duke of Windsor). Sale proceeds were dedicated to the Legion. The dozens of contributing artists and writers were among the most talented British subjects in their fields, including Winston Churchill, Rudyard Kipling, P.G. Wodehouse, Aldous Huxley, Vita Sackville-West, G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Augustus John, Eric Kennington, and John Nash. The book was edited by James Humphrey Cotton Minchin (1894-1966), a WWI veteran of the Cameronians and the Royal Flying Corps. Trade editions ran to multiple printings. There was also a 600 copy limited edition. 500 of these were signed by the editor and bound similarly to trade editions. But “the first 100 were reserved for H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, sponsor of the volume, in his gift.” These hundred were simply magnificent – printed in red and black by The Curwen Press on larger, hand-made paper, profusely illustrated, extravagantly bound in elaborate blind and gilt-tooled white pigskin. Massive volumes, they measure 13 x 10 x 2 inches and weigh 6.6 pounds. Each copy was hand-numbered.

These hundred were simply magnificent – printed in red and black by The Curwen Press on larger, hand-made paper, profusely illustrated, extravagantly bound in elaborate blind and gilt-tooled white pigskin. Massive volumes, they measure 13 x 10 x 2 inches and weigh 6.6 pounds. Each copy was hand-numbered. Winifred Austen

Winifred Austen Laurence Binyon

Laurence Binyon Sir Arthur Cope

Sir Arthur Cope David Garnett

David Garnett Dame Laura Knight

Dame Laura Knight Gilbert Murray

Gilbert Murray Charles Ricketts

Charles Ricketts Edith Sitwell

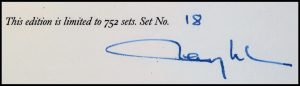

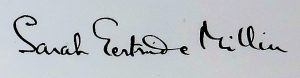

Edith Sitwell We will soon be pleased to offer an unusually fine example, copy “68”, hand-numbered thus on the limitation page. The binding and contents are nearly flawless.

We will soon be pleased to offer an unusually fine example, copy “68”, hand-numbered thus on the limitation page. The binding and contents are nearly flawless. Superlative condition owes to the presence of the original felt-lined cloth clamshell case, with a discreet, inked “No.68” on the upper front cover.

Superlative condition owes to the presence of the original felt-lined cloth clamshell case, with a discreet, inked “No.68” on the upper front cover.

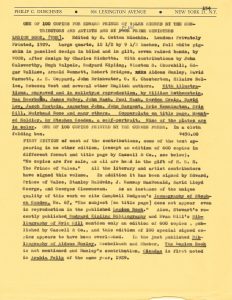

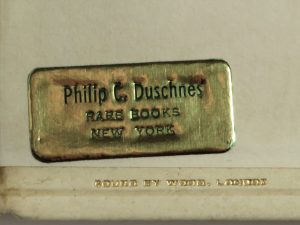

Laid in the case is an original description of this book by noted New York bookseller Philip C. Duschnes, who died in 1970. His tiny gilt sticker is affixed to the lower rear pastedown.

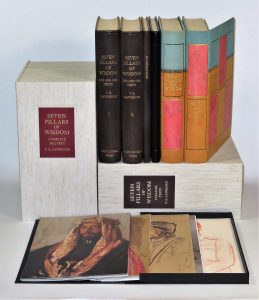

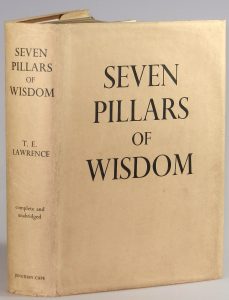

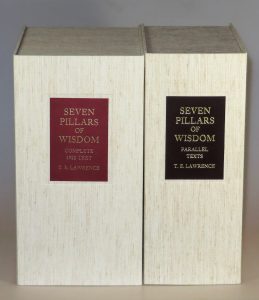

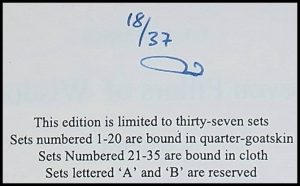

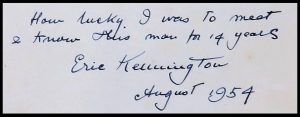

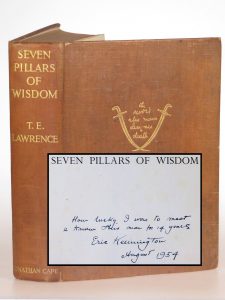

Laid in the case is an original description of this book by noted New York bookseller Philip C. Duschnes, who died in 1970. His tiny gilt sticker is affixed to the lower rear pastedown. Today, a first trade edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdomrendered special by a poignant inscription by Eric Kennington, the man who created thirty-one of the illustrations within its pages. Inked in blue in four lines on the half title, Kennington wrote: “How lucky I was to meet | & know this man for 14 years | Eric Kennington | August 1954”.

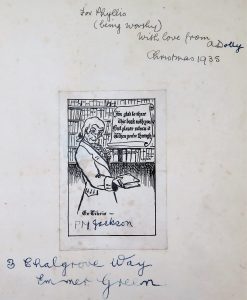

Today, a first trade edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdomrendered special by a poignant inscription by Eric Kennington, the man who created thirty-one of the illustrations within its pages. Inked in blue in four lines on the half title, Kennington wrote: “How lucky I was to meet | & know this man for 14 years | Eric Kennington | August 1954”. A gift inscription “For Phyllis” dated “Christmas 1935” is inked on the front free endpaper above the illustrated book plate of “PM Jackson”.

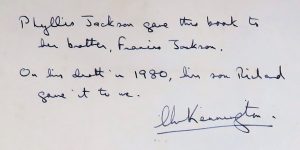

A gift inscription “For Phyllis” dated “Christmas 1935” is inked on the front free endpaper above the illustrated book plate of “PM Jackson”. A five-line inked notation on the front free endpaper verso that appears to be signed by Christopher Kennington (Eric Kennington’s son) reads: “Phyllis Jackson gave this book to | her brother, Francis Jackson. | On his death in 1980, his son Richard | gave it to me.”

A five-line inked notation on the front free endpaper verso that appears to be signed by Christopher Kennington (Eric Kennington’s son) reads: “Phyllis Jackson gave this book to | her brother, Francis Jackson. | On his death in 1980, his son Richard | gave it to me.” Eric Henri Kennington (1888-1960) was known as a painter, print maker, and sculptor and, most notably, as “a born painter of the nameless heroes of the rank and file” whom he portrayed during both the First and Second World War.

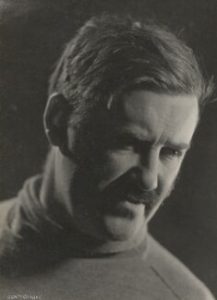

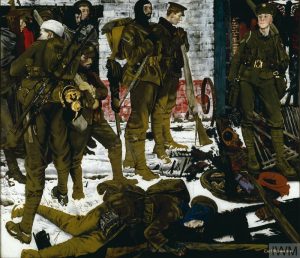

Eric Henri Kennington (1888-1960) was known as a painter, print maker, and sculptor and, most notably, as “a born painter of the nameless heroes of the rank and file” whom he portrayed during both the First and Second World War. Badly wounded on the Western Front in 1915, during his convalescence he produced The Kensingtons at Laventie, a portrait of a group of infantrymen. When exhibited in the spring of 1916 its portrayal of exhausted soldiers created a sensation. Kennington finished the war employed as a war artist by the Ministry of Information. After the war, he met T. E. Lawrence at an exhibition of Kennington’s war art.

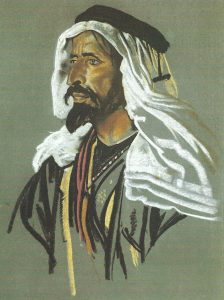

Badly wounded on the Western Front in 1915, during his convalescence he produced The Kensingtons at Laventie, a portrait of a group of infantrymen. When exhibited in the spring of 1916 its portrayal of exhausted soldiers created a sensation. Kennington finished the war employed as a war artist by the Ministry of Information. After the war, he met T. E. Lawrence at an exhibition of Kennington’s war art. In 1921, Kennington traveled to the Middle East with Lawrence where, Lawrence approvingly wrote of his work, “instinctively he drew the men of the desert.” Kennington served as art editor for Lawrence’s legendary 1926 Subscribers’ Edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdomand produced many of the drawings therein.

In 1921, Kennington traveled to the Middle East with Lawrence where, Lawrence approvingly wrote of his work, “instinctively he drew the men of the desert.” Kennington served as art editor for Lawrence’s legendary 1926 Subscribers’ Edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdomand produced many of the drawings therein. That same year he produced a bust of Lawrence – an image of which is the frontispiece of this book. On 15 February 1927, Lawrence wrote to Kennington praising the bust as “magnificent”. Lawrence said “It represents not me, but my top-moments, those few seconds in which I succeed in thinking myself right out of things.” In 1935, Kennington served as one of Lawrence’s pallbearers.

That same year he produced a bust of Lawrence – an image of which is the frontispiece of this book. On 15 February 1927, Lawrence wrote to Kennington praising the bust as “magnificent”. Lawrence said “It represents not me, but my top-moments, those few seconds in which I succeed in thinking myself right out of things.” In 1935, Kennington served as one of Lawrence’s pallbearers. In 1936 his second, memorial bust of Lawrence was installed in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Kennington was again an official war artist for the British government during the Second World War (Ministry of Information and Air Ministry), producing a large number of portraits of individual soldiers in addition to military scenes. Kennington died a member of the Royal Academy six years after writing the inscription in this book.

In 1936 his second, memorial bust of Lawrence was installed in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Kennington was again an official war artist for the British government during the Second World War (Ministry of Information and Air Ministry), producing a large number of portraits of individual soldiers in addition to military scenes. Kennington died a member of the Royal Academy six years after writing the inscription in this book. It was only in the summer of 1935, in the weeks following Lawrence’s death, that the text of the Subscribers’ Edition text was finally published for circulation to the general public in the form of a British first trade edition. This copy inscribed by Kennington is the first printing of this British first trade edition. Condition is good, showing the aesthetic flaws of age and wear, but sound. The khaki cloth binding is square and tight with wear to extremities, overall soiling and staining, and considerable scuffing to the rear cover. The contents are clean with toning to the page edges. A tiny Colchester bookseller sticker is affixed to the lower rear pastedown.

It was only in the summer of 1935, in the weeks following Lawrence’s death, that the text of the Subscribers’ Edition text was finally published for circulation to the general public in the form of a British first trade edition. This copy inscribed by Kennington is the first printing of this British first trade edition. Condition is good, showing the aesthetic flaws of age and wear, but sound. The khaki cloth binding is square and tight with wear to extremities, overall soiling and staining, and considerable scuffing to the rear cover. The contents are clean with toning to the page edges. A tiny Colchester bookseller sticker is affixed to the lower rear pastedown. Look for this and dozens of other signed or inscribed items in our “Extra Ink” catalogue late in 2018!

Look for this and dozens of other signed or inscribed items in our “Extra Ink” catalogue late in 2018!

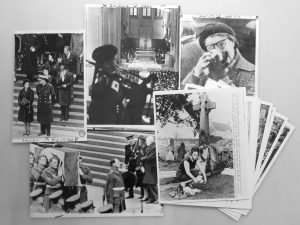

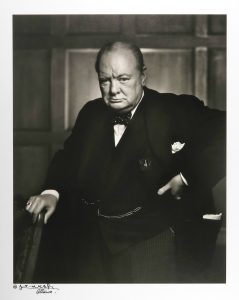

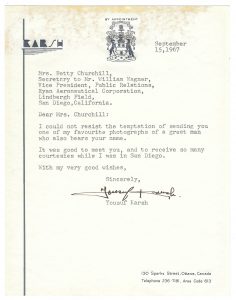

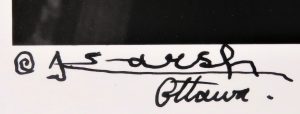

The photo itself is signed by Karsh in black in two lines on the lower left margin of the photo “© Y Karsh | Ottawa.” But in addition to Karsh’s signature, this photo comes with a presentation letter from Karsh typed on his Ottawa studio stationery and signed “Yousuf Karsh.” The letter is dated “September 15, 1967” and addressed: “Mrs. Betty Churchill, Secretary to Mr. William Wagner, Vice President, Public Relations, Ryan Aeronautical Corporation, Lindbergh Field, San Diego, California.”

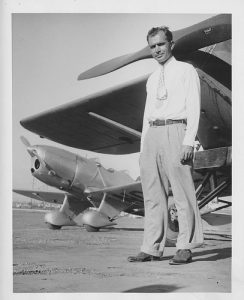

The photo itself is signed by Karsh in black in two lines on the lower left margin of the photo “© Y Karsh | Ottawa.” But in addition to Karsh’s signature, this photo comes with a presentation letter from Karsh typed on his Ottawa studio stationery and signed “Yousuf Karsh.” The letter is dated “September 15, 1967” and addressed: “Mrs. Betty Churchill, Secretary to Mr. William Wagner, Vice President, Public Relations, Ryan Aeronautical Corporation, Lindbergh Field, San Diego, California.” Tubal Claude Ryan (1898-1982) bought his first airplane, a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny, in San Diego in 1922, and began his aeronautical enterprises by charging for rides. By the late 1920s his aviation ventures included the nation’s first year-round regularly scheduled daily airline passenger service. In 1927, Ryan’s namesake company was tasked with building a single-engine plane that would be called The Spirit of St. Louis for a fellow named Charles Lindbergh.

Tubal Claude Ryan (1898-1982) bought his first airplane, a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny, in San Diego in 1922, and began his aeronautical enterprises by charging for rides. By the late 1920s his aviation ventures included the nation’s first year-round regularly scheduled daily airline passenger service. In 1927, Ryan’s namesake company was tasked with building a single-engine plane that would be called The Spirit of St. Louis for a fellow named Charles Lindbergh. After Lindberg’s historic solo flight, in 1928 Ryan founded The Ryan Aeronautical Corporation. This company, among many accomplishments, built the preeminent trainer aircraft used though the Second World War, the first jet-plus-propeller aircraft for the Navy, and the first successful vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, as well as pioneering remotely piloted vehicles and jet drones, Doppler systems, and lunar landing radar.

After Lindberg’s historic solo flight, in 1928 Ryan founded The Ryan Aeronautical Corporation. This company, among many accomplishments, built the preeminent trainer aircraft used though the Second World War, the first jet-plus-propeller aircraft for the Navy, and the first successful vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, as well as pioneering remotely piloted vehicles and jet drones, Doppler systems, and lunar landing radar. In 1969, just a few years after this photograph was signed and presented by Karsh, Ryan Aeronautical became Teledyne Ryan, a subsidiary of Teledyne, at an acquisition price of $128 million. Teledyne Ryan became, in turn, part of Northrop Grumman in 1999.

In 1969, just a few years after this photograph was signed and presented by Karsh, Ryan Aeronautical became Teledyne Ryan, a subsidiary of Teledyne, at an acquisition price of $128 million. Teledyne Ryan became, in turn, part of Northrop Grumman in 1999. Churchill’s speech of December 26, 1941 to a joint session of the U.S. Congress was sober, resolved, and eloquently defiant, but of course also featured the sparkle of Churchillian wit, which was irrepressible even in the dark hours of the war: “I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way around, I might have got here on my own.” His speech was also an important personal introduction to the elected leaders he needed to embrace the alliance so vital to his nation. A few days later, in his famous “Some chicken, some neck!” speech of December 30 to both houses of the Canadian Parliament, Churchill was characteristically defiant: “When I warned them that Britain would fight alone whatever they did, their generals told their Prime Minister and his divided Cabinet ‘In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken.’ Some chicken; some neck.”

Churchill’s speech of December 26, 1941 to a joint session of the U.S. Congress was sober, resolved, and eloquently defiant, but of course also featured the sparkle of Churchillian wit, which was irrepressible even in the dark hours of the war: “I cannot help reflecting that if my father had been American and my mother British, instead of the other way around, I might have got here on my own.” His speech was also an important personal introduction to the elected leaders he needed to embrace the alliance so vital to his nation. A few days later, in his famous “Some chicken, some neck!” speech of December 30 to both houses of the Canadian Parliament, Churchill was characteristically defiant: “When I warned them that Britain would fight alone whatever they did, their generals told their Prime Minister and his divided Cabinet ‘In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken.’ Some chicken; some neck.” Born in Armenian Turkey, Karsh had fled on foot with his family to Syria before immigrating to Canada in 1924 as a refugee. After apprenticing with the celebrity portrait photographer John H. Garo, Karsh moved to Ottawa, where he opened a portrait studio with the intent of photographing “people of consequence.” His breakthrough came in 1936 when he photographed the meeting between U.S. President

Born in Armenian Turkey, Karsh had fled on foot with his family to Syria before immigrating to Canada in 1924 as a refugee. After apprenticing with the celebrity portrait photographer John H. Garo, Karsh moved to Ottawa, where he opened a portrait studio with the intent of photographing “people of consequence.” His breakthrough came in 1936 when he photographed the meeting between U.S. President  Printing date is established by the letter and the fact that Karsh stopped signing his photos with “Ottawa” in the late 1960s. The image verso bears the studio stamp of Karsh’s Ottawa studio reading “COPYRIGHT | the following copyright must be used | © Karsh, Ottawa” as well as a penciled “P of G” notation referring to the image’s inclusion in Karsh’s book Portraits of Greatness(1959).

Printing date is established by the letter and the fact that Karsh stopped signing his photos with “Ottawa” in the late 1960s. The image verso bears the studio stamp of Karsh’s Ottawa studio reading “COPYRIGHT | the following copyright must be used | © Karsh, Ottawa” as well as a penciled “P of G” notation referring to the image’s inclusion in Karsh’s book Portraits of Greatness(1959).

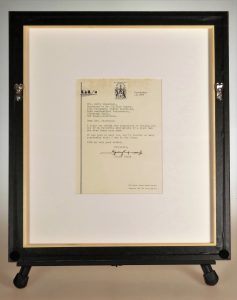

We deliberately chose not to frame in the conventional manner, with the photo matted and framed beside the letter. The photo is simply too striking an image to warrant the aesthetic distraction of the letter right beside it. Instead, we commissioned a custom, double-sided frame using museum quality, archival materials. The solid walnut frame is stained dark black with a thick 8-ply rag board mat for added depth and richness and is glazed with UV filtering acrylic. On the reverse the letter has also been matted and glazed. The framed piece measures 17.375 x 15.375 inches (44.1 x 39 cm).

We deliberately chose not to frame in the conventional manner, with the photo matted and framed beside the letter. The photo is simply too striking an image to warrant the aesthetic distraction of the letter right beside it. Instead, we commissioned a custom, double-sided frame using museum quality, archival materials. The solid walnut frame is stained dark black with a thick 8-ply rag board mat for added depth and richness and is glazed with UV filtering acrylic. On the reverse the letter has also been matted and glazed. The framed piece measures 17.375 x 15.375 inches (44.1 x 39 cm).

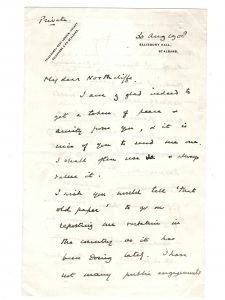

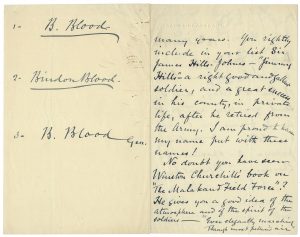

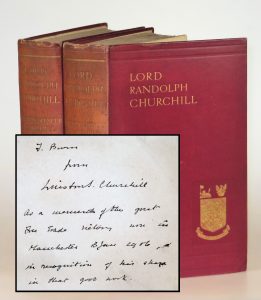

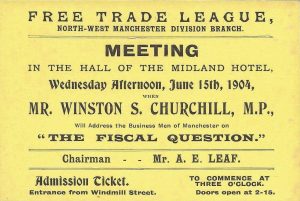

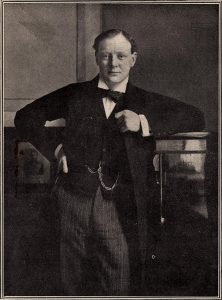

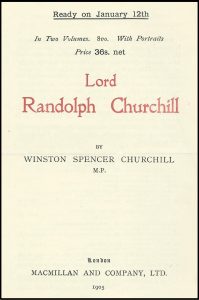

On 31 May 1904 Churchill left his father’s Conservative Party, crossing the aisle to become a Liberal, beginning a dynamic chapter in his political career that saw him champion progressive causes and branded a traitor to his class. On 2 January 1906 Churchill published his two-volume biography of his father. Immediately thereafter, he campaigned for eight days in North-West Manchester, hoping to win his first election as a Liberal.

On 31 May 1904 Churchill left his father’s Conservative Party, crossing the aisle to become a Liberal, beginning a dynamic chapter in his political career that saw him champion progressive causes and branded a traitor to his class. On 2 January 1906 Churchill published his two-volume biography of his father. Immediately thereafter, he campaigned for eight days in North-West Manchester, hoping to win his first election as a Liberal. Churchill’s defection from the Conservative Party was much on the minds of the voters. His father’s history was much on his own mind. To the charge of being a political turncoat, Churchill replied: “I admit I have changed my Party. I don’t deny it. I am proud of it. When I think of all of the labours Lord Randolph Churchill gave to the fortunes of the Conservative Party and the ungrateful way he was treated by them when they obtained the power they would never have had but for him, I am delighted that circumstances have enabled me to break with them while I am still young, and still have the best energies of my life to give to the popular cause.”

Churchill’s defection from the Conservative Party was much on the minds of the voters. His father’s history was much on his own mind. To the charge of being a political turncoat, Churchill replied: “I admit I have changed my Party. I don’t deny it. I am proud of it. When I think of all of the labours Lord Randolph Churchill gave to the fortunes of the Conservative Party and the ungrateful way he was treated by them when they obtained the power they would never have had but for him, I am delighted that circumstances have enabled me to break with them while I am still young, and still have the best energies of my life to give to the popular cause.” North-West Manchester would prove a brief and fraught interlude in Churchill’s six-decade Parliamentary career, his shortest relationship among the five constituencies he ultimately held. In 1908 when Churchill was appointed to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade, custom required that he submit to re-election. His by-election became a test of confidence in the Liberal government. Forced to defend the Government’s policies, targeted by vengeful Conservatives, and hounded on the hustings by Suffragettes, Churchill was narrowly defeated by the Conservative candidate.

North-West Manchester would prove a brief and fraught interlude in Churchill’s six-decade Parliamentary career, his shortest relationship among the five constituencies he ultimately held. In 1908 when Churchill was appointed to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade, custom required that he submit to re-election. His by-election became a test of confidence in the Liberal government. Forced to defend the Government’s policies, targeted by vengeful Conservatives, and hounded on the hustings by Suffragettes, Churchill was narrowly defeated by the Conservative candidate. Nonetheless, the 13 January 1906 election and Churchill’s brief time as M.P. for North-West Manchester made all things possible for him. At 31 years old, “Churchill was now a Junior Minister in a Government furnished with far greater authority than it had expected.” Disraeli’s biographer wrote to congratulate Churchill “both on his book and the beginning of his official career”.

Nonetheless, the 13 January 1906 election and Churchill’s brief time as M.P. for North-West Manchester made all things possible for him. At 31 years old, “Churchill was now a Junior Minister in a Government furnished with far greater authority than it had expected.” Disraeli’s biographer wrote to congratulate Churchill “both on his book and the beginning of his official career”. All this was as yet unseen when he won his first seat as a Liberal in North-West Manchester on 13 January 1906. Nonetheless, we can reasonably speculate that the importance of the victory was not lost upon Churchill. Churchill’s biography of his father had helped place Lord Randolph in historical context. We can also speculate that Churchill’s electoral victory as a Liberal in North-West Manchester helped Churchill put the specter of Lord Randolph’s failed political career behind him. Perhaps all of this was in Churchill’s mind – or perhaps he was simply grateful – when he paused to warmly inscribe this first edition of his newly published book to the man who helped him achieve success. Irrespective, this presentation set testifies to the remarkable convergences of a pivotal moment in the life of both ascending Winstons – the literary and the political.

All this was as yet unseen when he won his first seat as a Liberal in North-West Manchester on 13 January 1906. Nonetheless, we can reasonably speculate that the importance of the victory was not lost upon Churchill. Churchill’s biography of his father had helped place Lord Randolph in historical context. We can also speculate that Churchill’s electoral victory as a Liberal in North-West Manchester helped Churchill put the specter of Lord Randolph’s failed political career behind him. Perhaps all of this was in Churchill’s mind – or perhaps he was simply grateful – when he paused to warmly inscribe this first edition of his newly published book to the man who helped him achieve success. Irrespective, this presentation set testifies to the remarkable convergences of a pivotal moment in the life of both ascending Winstons – the literary and the political.