Winston S. Churchill may well be one of the most well-known, studied, quoted, and collected figures of twentieth century leadership and literature.

This means that even though we are privileged to handle some of the most interesting and rare Churchill material in the world, we seldom encounter items that are truly unique, previously unknown, or potentially significant to the historical record.

The item we are writing about today is all three – an apparently singular item and a rather remarkable discovery.

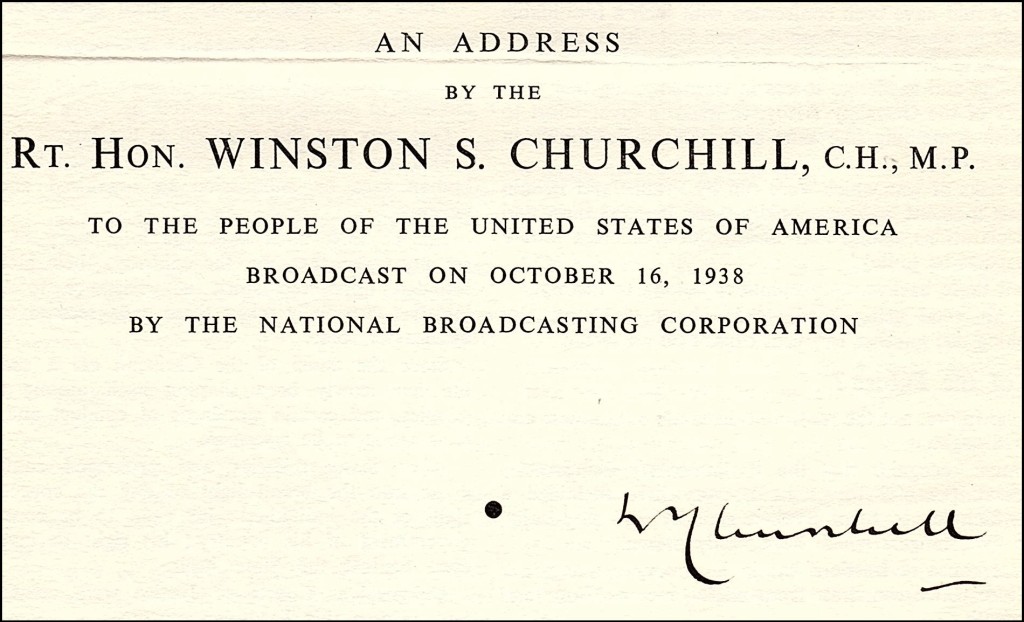

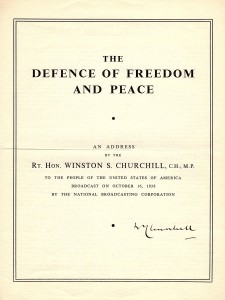

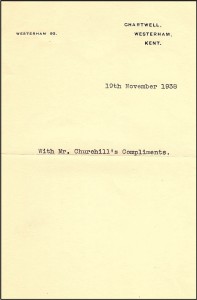

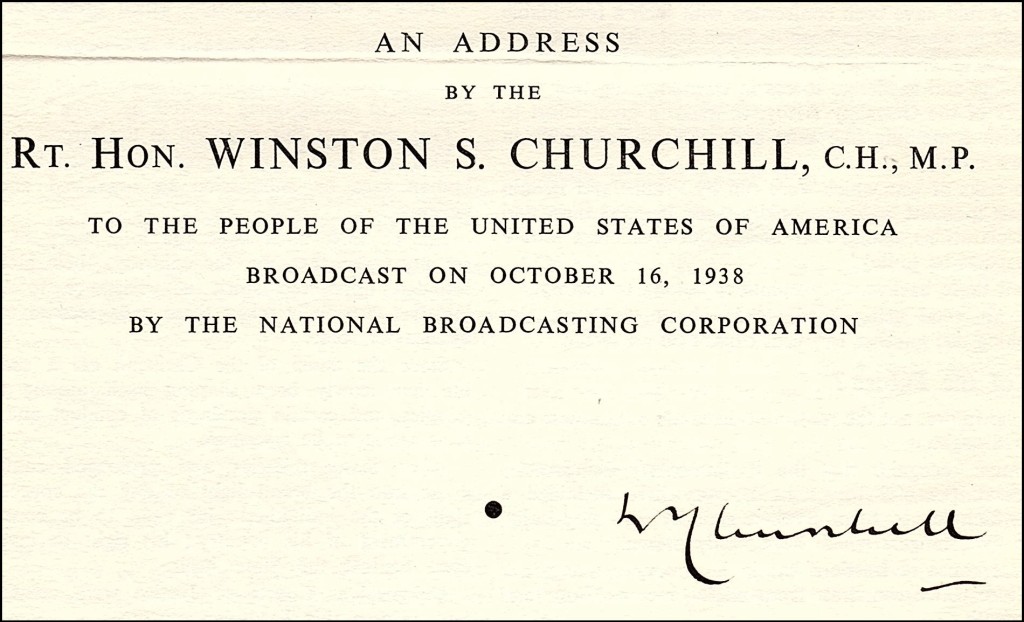

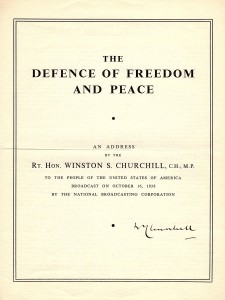

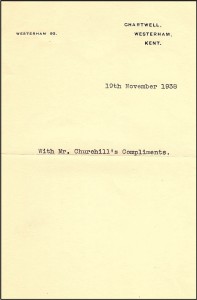

This is a previously unknown publication of Churchill’s 16 October 1938 address to the American people about the Munich Agreement. Prior to this discovery, no contemporary stand-alone publication of this speech was known. There is no doubt that this publication was contemporary, as it is accompanied by a slip on Churchill’s Chartwell stationery printed: “19th November 1938 | With Mr. Churchill’s compliments.” As we discuss in this post, it may have even been printed prior to delivery of the speech. This copy bears substantial textual and format differences from the speech as hand-emended and delivered by Churchill, and as subsequently published. Finally, it is not just the only known copy to survive of a textually unique edition, it is also signed by Churchill in bold black ink on the front cover.

The Speech

On 30 September 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned from meeting with Hitler in Munich to announce that he had ceded Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland to the Nazis in return for “peace in our time.”

On 30 September 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned from meeting with Hitler in Munich to announce that he had ceded Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland to the Nazis in return for “peace in our time.”

After receiving the news, Churchill paused with a friend outside of a restaurant from which echoed the sounds of laughter. Churchill “stopped in the doorway, watching impassively.” Turning away, “he muttered ‘those poor people! They little know what they will have to face.’” (Gilbert, Vol. V, p.990)

Churchill was both weary and desperately worried. “He was sixty-three years old, and the strain of his five-year campaign… had begun to take its toll.” (Gilbert, Vol. V, p.961) As he had told the House of Commons in March when speaking about Czechoslovakia, “For five years I have talked to the House on these matters – not with very great success. I have watched this famous island descending incontinently, fecklessly, the stairway which leads to a dark gulf.”

Privately, Churchill’s feelings were even more deeply disturbed. He wrote to Lord Moyne on 11 September: “Owing to the neglect of our defences and the mishandling of the German problem during the last five years, we seem to be very near the bleak choice between War and Shame. My feeling is that we shall chose Shame, and then have War thrown in a little later on even more adverse terms…” Of the time, Churchill’s biographer, Martin Gilbert, wrote: “For the first time in his political career – and it was nearly forty years since he had first stood for Parliament – Churchill’s optimism deserted him. Despite his appeal in Parliament for a national revival, the events of September 1938 filled him with a deep despondency…” (Gilbert, Vol. V, p.1007)

On 16 October 1938, NBC broadcast an address by Churchill directly to the American people. It may seem odd that Churchill – merely a Member of Parliament and representative of neither his Party nor his Government – would address the people of the United States. The fact is that Churchill’s tireless campaigning for prudent rearmament and collective security had given him a voice and audience independent of his Government. By this time, it was almost as if Churchill was Leader of the Opposition, despite sharing the party of the sitting Prime Minister. Churchill now used his personal platform to redouble his efforts to rouse Britain and America.

Churchill’s speech was a boldly unequivocal statement of the situation. “As a result of the Munich debate, relations between Churchill and Chamberlain had worsened considerably.” (Gilbert, Vol. V, p.1008) Whereas Churchill might have shown a modicum of restraint even a few weeks earlier, Munich was a breaking point – for him, for Chamberlain, and for the ever worsening strategic situation in Europe. Sixteen days after Munich, Nazi Germany had not only occupied the Sudetenland, but exceeded the agreed boundaries and begun carrying out its customary Gestapo pogroms.

All of which is to say Churchill did not hold back. To convey the dire nature of the situation and set the tone, he began “I avail myself with relief of the opportunity of speaking to the people of the United States. I do not know how long such liberties will be allowed… Let me, then, speak with truth and earnestness while time remains.”

Churchill frontally assaulted both the moral and strategic infirmity of the Munich agreement. “All the world wishes for peace and security. Have we gained it by the sacrifice of the Czechosolvak Republic… the model democratic State of Central Europe… has been deserted, destroyed, and devoured… Is this the end, or is there more to come?… Can peace, goodwill and confidence be built upon submission to wrong-doing backed by force?”

Sensitive to both America’s isolationist sentiment and its proud sense of democratized progress, Churchill couched the present in terms of both the wartime threats and failures of the past and the nature of the impending future. “The culminating question to which I have been leading is whether… the world of increasing hope and enjoyment for the common man, the world of honoured tradition and expanding science – should meet this menace by submission or by resistance.”

Though he spoke of history and moral imperative, he did not eschew blunt practicality. “We are left in no doubt where American conviction and sympathies lie: but will you wait until British freedom and independence have succumbed, and then take up the cause when it is three-quarters ruined, yourselves alone?… We shall do it in the end. But how much harder our toil for every day’s delay!”

Churchill was well aware that his calls to action were pejoratively characterized as war-mongering. Hence the title of the speech – “The Defence of Freedom and Peace.” Hence also his rhetorical inoculation against the charge: “Is this a call to war? …I declare it to be the sole guarantee of peace. We need the swift gathering of forces to confront not only military but moral aggression; the resolute and sober acceptance of their duty by the English-speaking peoples…”

A year later, in September 1939, Churchill returned to the Admiralty. He replaced Chamberlain as Prime Minister in May 1940. America would not formally enter the war until December 1941, but until she did Churchill’s relationship with America and her President, and the vital material support it brought, enabled Britain to survive.

The Pamphlet

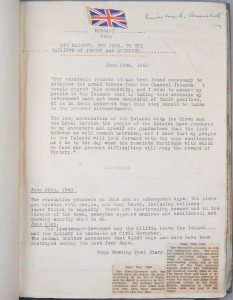

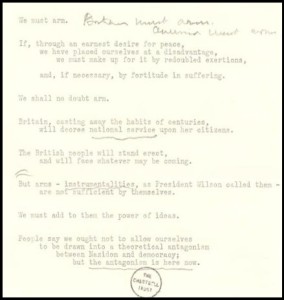

This pamphlet is in four-page folded leaflet format, the front cover as title page with text on pages 2-4, drop-head title at page 2, printer information on the lower right corner of the fourth and final page, and subject sub-headings in bold punctuating the text.

This pamphlet is in four-page folded leaflet format, the front cover as title page with text on pages 2-4, drop-head title at page 2, printer information on the lower right corner of the fourth and final page, and subject sub-headings in bold punctuating the text.

It is quite striking and unusual for a speech pamphlet publication in several respects. First, it is large, measuring 11.25 x 8.75 inches. Rather than being printed on thin, wove paper, it is printed on substantial and good quality, watermarked, laid paper. The layout features paragraph breaks for nearly every individual sentence, more analogous to the famous ‘psalm form’ in which Churchill printed his speech notes, rather than to the more conventional, condensed paragraph format of published versions. Although the printer is specified (“St. Clements Press Ltd, Portugal St., Kingsway, London, W.C.2.), no publisher is specified.

It is quite striking and unusual for a speech pamphlet publication in several respects. First, it is large, measuring 11.25 x 8.75 inches. Rather than being printed on thin, wove paper, it is printed on substantial and good quality, watermarked, laid paper. The layout features paragraph breaks for nearly every individual sentence, more analogous to the famous ‘psalm form’ in which Churchill printed his speech notes, rather than to the more conventional, condensed paragraph format of published versions. Although the printer is specified (“St. Clements Press Ltd, Portugal St., Kingsway, London, W.C.2.), no publisher is specified.

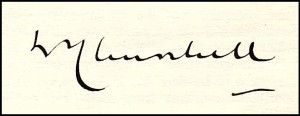

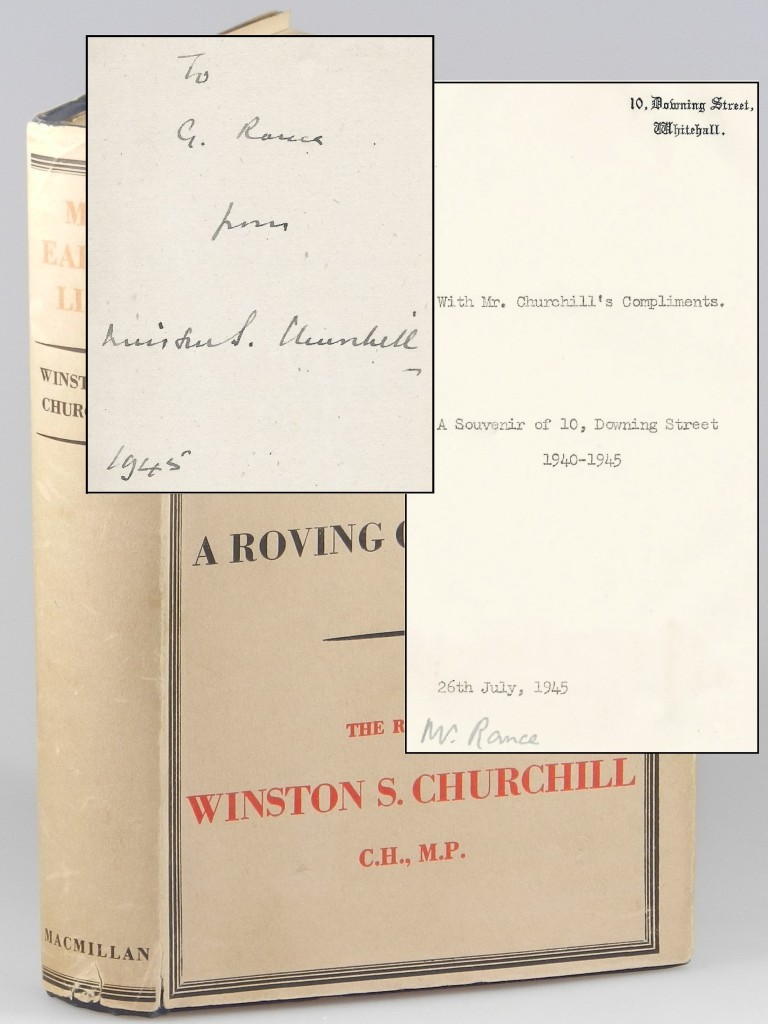

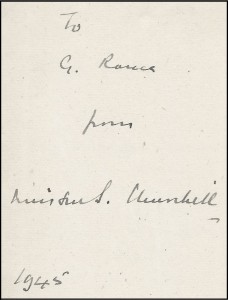

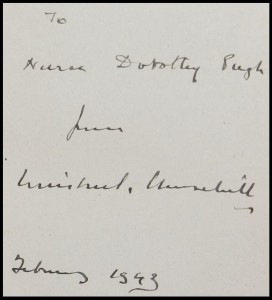

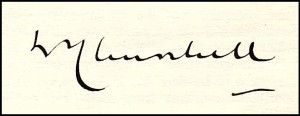

Churchill’s signature is boldly inked in black on the lower right front cover in a style we have previously catalogued spanning the 1920s to the 1940s and observed as not uncommon to his 1930s signatures, namely “WChurchill” with the final letters of his surname underscored.

Churchill’s signature is boldly inked in black on the lower right front cover in a style we have previously catalogued spanning the 1920s to the 1940s and observed as not uncommon to his 1930s signatures, namely “WChurchill” with the final letters of his surname underscored.

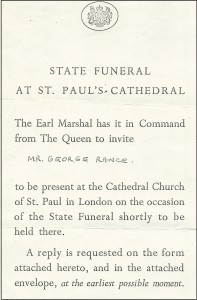

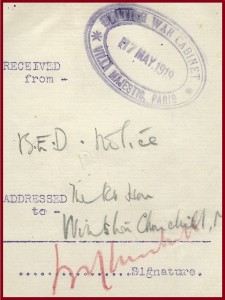

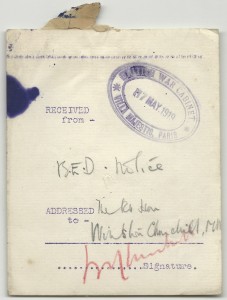

Accompanying the pamphlet is a sheet of Churchill’s Chartwell stationery printed in two lines: “19th November 1938 | With Mr. Churchill’s Compliments.” 19 November 1938 was a Saturday, which would have found Churchill staying at Chartwell for the weekend. “Throughout the spring and summer of 1938 Churchill spent as much time as possible at Chartwell.” (Gilbert, Vol. V, p.958)

Accompanying the pamphlet is a sheet of Churchill’s Chartwell stationery printed in two lines: “19th November 1938 | With Mr. Churchill’s Compliments.” 19 November 1938 was a Saturday, which would have found Churchill staying at Chartwell for the weekend. “Throughout the spring and summer of 1938 Churchill spent as much time as possible at Chartwell.” (Gilbert, Vol. V, p.958)

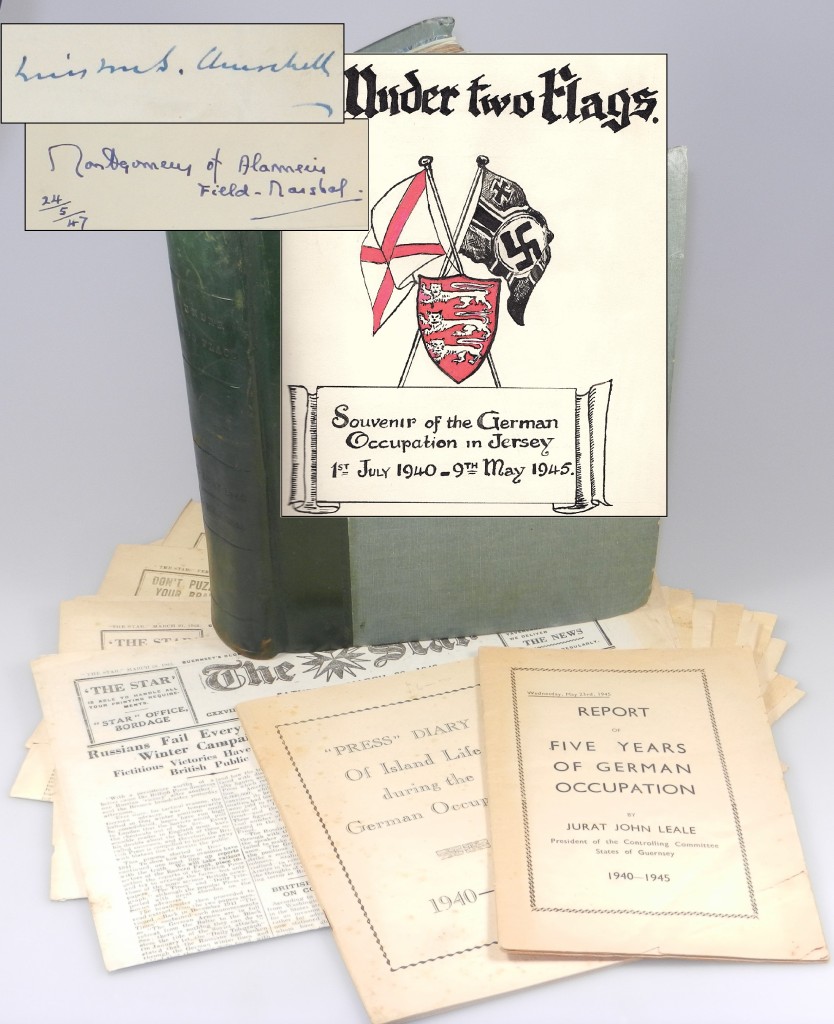

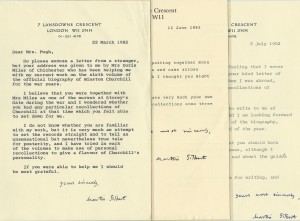

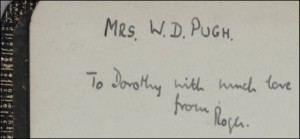

The signed pamphlet and accompanying compliments slip were acquired from the descendant of the original recipient, who held a significant and diverse collection of autograph material.

Differences between the pamphlet and Churchill’s corrected speech notes and delivered speech

Churchill often made revisions to his speeches until the final moments preceding delivery, including this specific speech. Courtesy of The Churchill Archives Centre, we have reviewed Churchill’s hand-corrected delivery notes for this speech. Comparison of this pamphlet’s text to Churchill’s original speech notes reveal a number of hand-made emendations to the speech as delivered which are not incorporated into this printed pamphlet. These differences (excepting minor and obvious spelling or transcription errors and small punctuation differences) are detailed in the table below.

| In Speech Notes |

In the Defence of Freedom and Peace Pamphlet |

Comment |

Location References |

| Notes Page |

Pamphlet Page / Column |

| the French and British peoples have yet done |

the French and British peoples have done |

‘yet’ added by hand in notes |

1 |

2 / Left |

| It is no good using hard words among friends |

It is no good using hard words |

‘among friends’ added by hand in notes |

3 |

2 / Left |

| will bring upon the world a blessing or a curse |

Will bring a blessing or a curse upon the world |

‘upon the world’ circled and moved to a new location in notes |

4 |

2 / Right |

| And then on top of all |

But then on top of all |

‘But’ is crossed out by hand in notes, changed to “And’ |

8 |

3 / Left |

| (to quote the current jargon) |

To quote the current jargon |

Parenthesis added by hand in notes |

9 |

3 / Right |

| A substantial five-sentence passage – essentially the “hard-sell” to the American people, beginning with the line “Far away, happily protected by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, you, the people of the United States…” |

Same |

Appears as the final paragraph in the pamphlet but was relocated closer to the mid-point of the speech when delivered. This is the greatest substantive difference between the printed pamphlet and the delivered speech. |

11 |

4 / Right |

| For after all |

Yet after all |

Difference in printed text |

12 |

3 / Right |

| they have but to be combined to be obeyed |

They have but to be united to be obeyed |

‘united’ is crossed out by hand in notes, changed to ‘combined’ |

12 |

3 / Right |

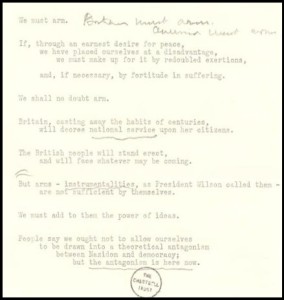

| We must arm. Britain must arm. America must arm. |

We must arm. |

Additional two sentences in noted added by hand |

13 |

4 / Left |

| make up for it by redoubled exertions |

Make up for it by redoubling exertions |

Difference in printed text |

13 |

4 / Left |

| But how much harder our toil for every day’s delay |

But how much harder our toil the longer the delay |

‘the longer the delay’ crossed out by hand in notes, new phrase added by hand |

15 |

4 / Right |

| Does anyone pretend that preparation for resistance to aggression is unleashing war? |

|

This phrase not present in the pamphlet was added by hand in the notes |

16 |

4 / Right |

| The swift and organized gathering of forces |

The swift and resolute gathering of forces |

‘resolute’ crossed out by hand in notes, ‘organized’ written above |

16 |

4 / Right |

| the fear which already darkens the sunlight to hundreds of millions of men |

the fear which already darkens the sunlight to millions of men |

‘millions of men’ is crossed out by hand in the notes, the phrase ‘to hundreds of millions of men’ added by hand |

16 |

4 / Right |

Among numerous small, substantive differences between the pamphlet and the speech as delivered and later published is inclusion of two notably blunt lines which the original speech notes show were added by hand by Churchill to the final draft: “Britain must arm. America must arm.”

Most significant among the changes to the version Churchill delivered on 16 October is the conclusion. A substantial five-sentence passage – essentially the “hard-sell” to the American people, beginning with the line “Far away, happily protected by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, you, the people of the United States…” – appears as the final paragraph in the pamphlet but was relocated closer to the mid-point of the speech when delivered.

Speculation about the origin and publication of the pamphlet

While evidence supports a conclusion that the pamphlet was printed prior to delivery of the speech, the dated compliments slip definitively bounds the publication date.

The pamphlet features numerous and noteworthy textual differences from the speech as delivered on 16 October and versions printed subsequently, notably in its first volume publication in a work by Churchill (Into Battle in February 1941).

At this time, evidence available supports speculation that this edition was printed for Churchill prior to delivery of the speech using a late-stage draft of Churchill’s speech notes.

Evidence considered includes:

- The format of the speech is uncommonly large for a speech pamphlet and printed on unusually thick, quality watermarked laid paper.

- While a printer is noted on the lower right rear cover, no publisher is specified.

- The layout of the speech with paragraph breaks for nearly every sentence is more analogous to the manner in which Churchill laid out his speeches for delivery than the more conventional, condensed paragraph format of the final version printed in Into Battle and subsequent publications. Spacing speech lines almost as verses rather than narrative text, Churchill used a distinctive ‘speech form’ or ‘psalm form’ for his speeches for more than half a century. (Gilbert, Vol VIII, p. 1120)

- Churchill is known to have made emendations and revisions to his speeches up until the final moments preceding delivery, including this specific speech. (Churchill’s original typed notes with his hand-made emendations are held by The Chartwell Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge, and the text of these original notes is printed in Gilbert, Companion Volume V, Part 3, at pages 1216-1227.)

Line-by-line comparison of the pamphlet speech text to the notes of the speech as delivered by Churchill reveal substantive differences between the printed pamphlet text and the speech as delivered. Many of these revisions and additions were made by hand in Churchill’s speech notes.

Line-by-line comparison of the pamphlet speech text to the notes of the speech as delivered by Churchill reveal substantive differences between the printed pamphlet text and the speech as delivered. Many of these revisions and additions were made by hand in Churchill’s speech notes.

Typos within the speech pamphlet, as well as the numerous and substantive differences from the final text, may explain why no other copies are known. Copies may have been distributed only by Churchill. Changes made to final version of the speech not reflected in the pamphlet would ostensibly have prevented either a large print run or any subsequent editions. The notionally limited distribution, coupled with the large size and comparatively perishable nature of the publication, would help to explain why we find no record of any other copies known to Churchill’s bibliographers or collectors.

While evidence supports a conclusion that the pamphlet was printed prior to delivery of the speech, there is no doubt that it was printed not long thereafter; the presence of the dated “19th November 1938” compliments slip on Chartwell stationery definitively bounds the publication date between mid-October and mid-November 1938.

Condition

Condition of the pamphlet is superb. We note no loss, tears, appreciable wear or soiling. A hint of toning and a horizontal crease – ostensibly from when the speech was originally posted – are the only signs of age and handling. The compliments slip on Chartwell stationery is in identical condition, showing only a neat horizontal crease and mild age-toning.

We will supply scans of the pamphlet upon request.

We are pleased to offer this singular and significant item to the collecting community HERE.

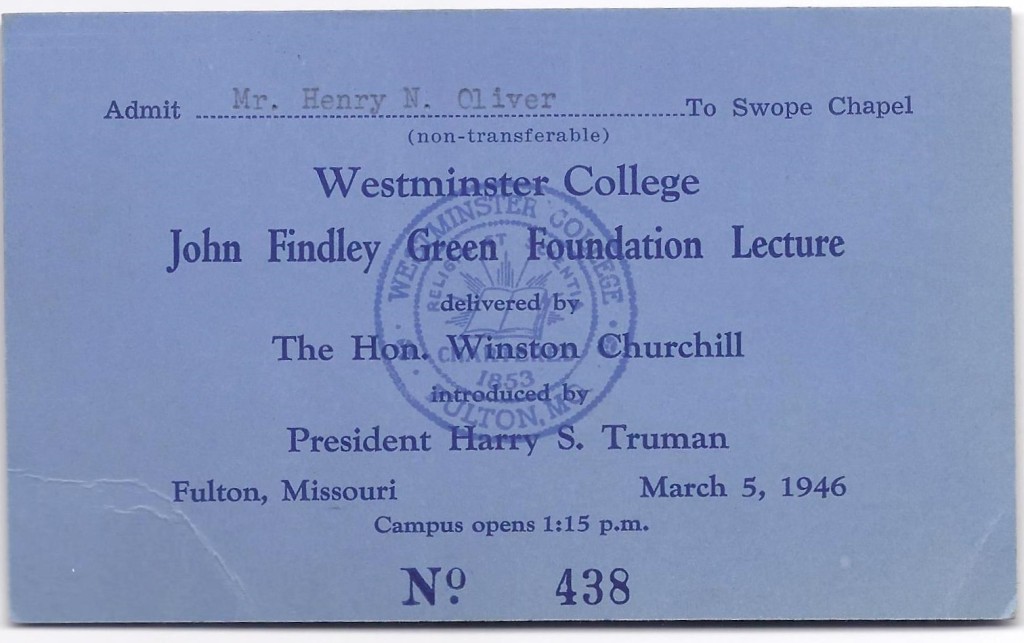

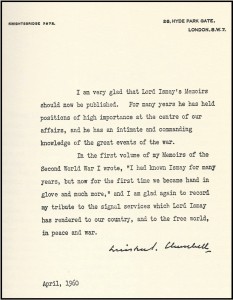

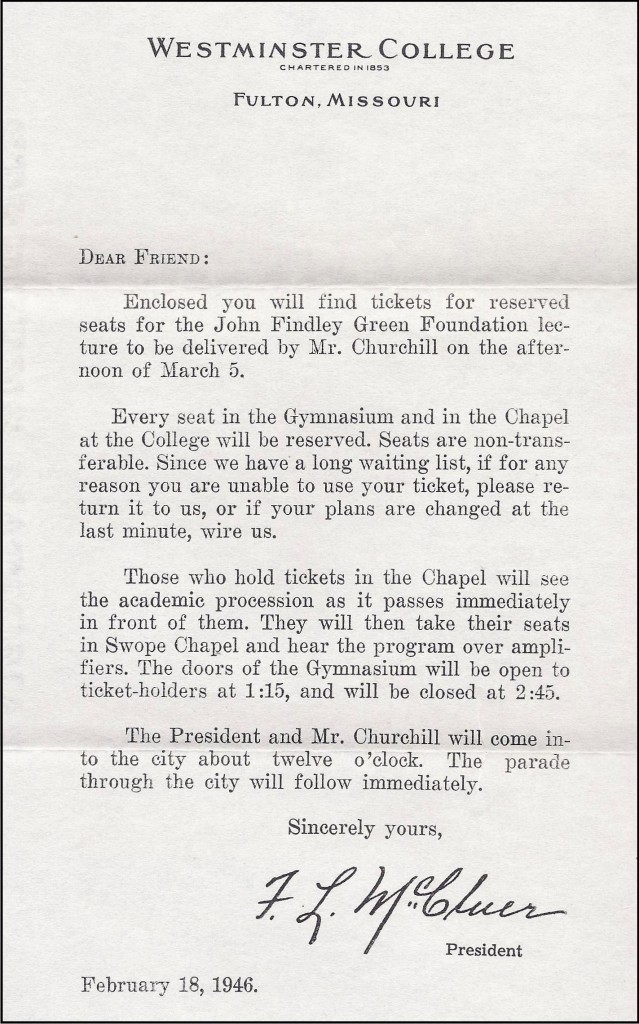

Then-President Harry S. Truman traveled with Churchill by special train from Washington D.C. for the twenty four hour overnight journey to Jefferson City, Missouri specifically to introduce Churchill in Fulton. With them was Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy. During the journey, the three men discussed recent Soviet provocations in northern Persia and Turkey. “During the morning of March 5, as the train continued westward along the Missouri river, Churchill completed his speech for Fulton. It was then mimeographed on the train, and a copy shown to Truman” who told Churchill that he “thought it was admirable” and “would do nothing but good, though it would make a stir.” (Gilbert, Vol. VIII, pp.196-197).

Then-President Harry S. Truman traveled with Churchill by special train from Washington D.C. for the twenty four hour overnight journey to Jefferson City, Missouri specifically to introduce Churchill in Fulton. With them was Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy. During the journey, the three men discussed recent Soviet provocations in northern Persia and Turkey. “During the morning of March 5, as the train continued westward along the Missouri river, Churchill completed his speech for Fulton. It was then mimeographed on the train, and a copy shown to Truman” who told Churchill that he “thought it was admirable” and “would do nothing but good, though it would make a stir.” (Gilbert, Vol. VIII, pp.196-197). Upon arriving in Jefferson City shortly before noon on March 5, Churchill, Truman, and Leahy drove to Fulton, where they met and lunched with Dr. Franc L. McCluer, the College president, before the academic procession and delivery of the speech. Though the subject of the speech was of utmost gravity, Churchill began with characteristic wit: “The name ‘Westminster’ is somehow familiar to me. I seem to have heard of it before.” The speech was broadcast throughout the United States.

Upon arriving in Jefferson City shortly before noon on March 5, Churchill, Truman, and Leahy drove to Fulton, where they met and lunched with Dr. Franc L. McCluer, the College president, before the academic procession and delivery of the speech. Though the subject of the speech was of utmost gravity, Churchill began with characteristic wit: “The name ‘Westminster’ is somehow familiar to me. I seem to have heard of it before.” The speech was broadcast throughout the United States. We were excited recently to offer an original ticket to Churchill’s speech, as well as an accompanying invitation letter signed by College President Franc L. McCluer. We had never before offered an original ticket and this is no surprise. In his invitation letter, McCluer specifically stated: “Every seat in the Gymnasium and in the Chapel at the College will be reserved. Seats are non-transferable. Since we have a long waiting list, if for any reason you are unable to use your ticket, please return it to us, or if your plans are changed at the last minute, wire us.”

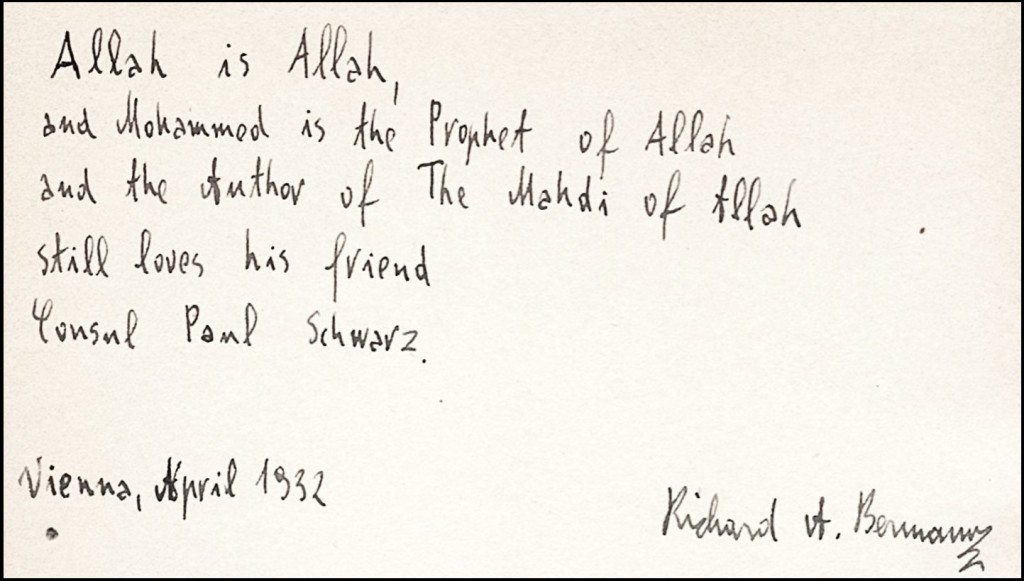

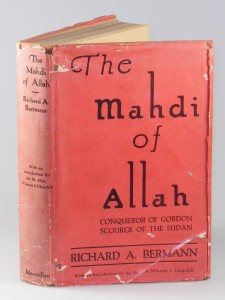

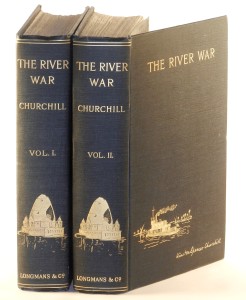

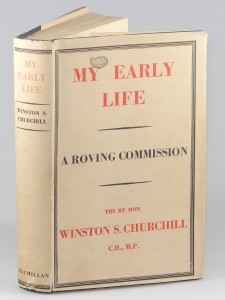

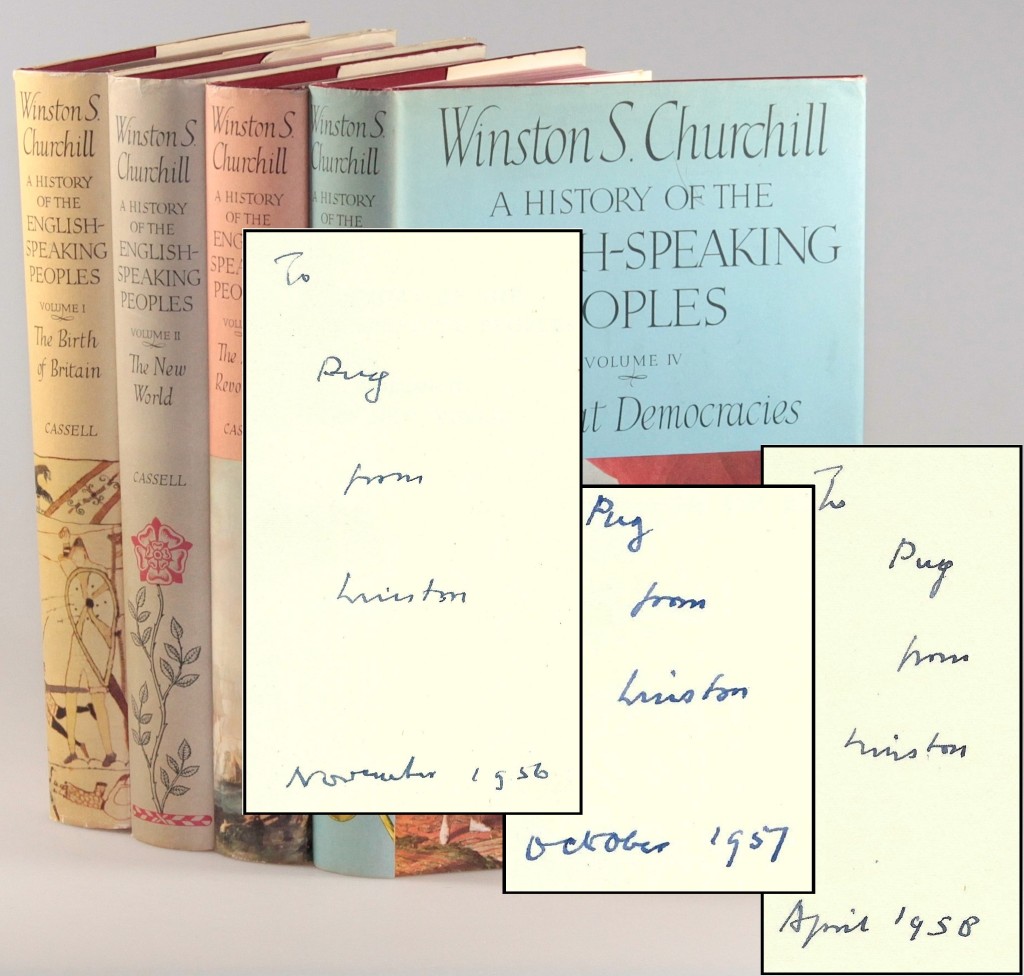

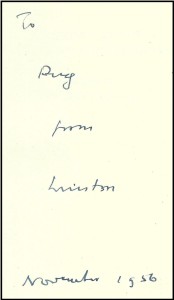

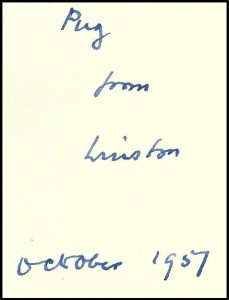

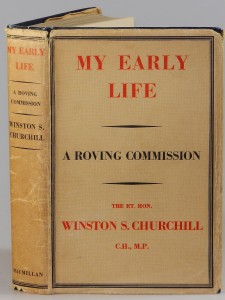

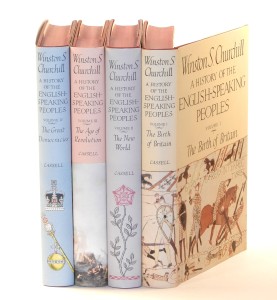

We were excited recently to offer an original ticket to Churchill’s speech, as well as an accompanying invitation letter signed by College President Franc L. McCluer. We had never before offered an original ticket and this is no surprise. In his invitation letter, McCluer specifically stated: “Every seat in the Gymnasium and in the Chapel at the College will be reserved. Seats are non-transferable. Since we have a long waiting list, if for any reason you are unable to use your ticket, please return it to us, or if your plans are changed at the last minute, wire us.” The cultural commonality and vitality of English-speaking peoples animated Churchill from his Victorian youth in an ascendant British Empire to his twilight in the midst of the American century. In fact, Churchill’s great four-volume work, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, was actually drafted in the 1930s. Fittingly, the half a million word draft was set aside when Churchill returned to the Admiralty and to war in September 1939. The war would, of course, pivot on an unprecedented alliance among the English-speaking peoples – an alliance Churchill personally did much to cultivate, cement, and sustain.

The cultural commonality and vitality of English-speaking peoples animated Churchill from his Victorian youth in an ascendant British Empire to his twilight in the midst of the American century. In fact, Churchill’s great four-volume work, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, was actually drafted in the 1930s. Fittingly, the half a million word draft was set aside when Churchill returned to the Admiralty and to war in September 1939. The war would, of course, pivot on an unprecedented alliance among the English-speaking peoples – an alliance Churchill personally did much to cultivate, cement, and sustain.